In his 1985 book, The Dental Physician (1), dentist Alfred Fonder, DDS, presents a series of case studies showing the integrated posture between the feet, legs, pelvis, lumbar spine, thoracic spine, cervical spine and temporomandibular joint.

His message is simple: a mechanical problem in any one part of the human body will affect and cause mechanical problems in the entire kinetic chain of alignment and motion.

The entire body is mechanically integrated.

••••

In 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen discovered x-rays and radiographs. For this discovery, in 1901, he was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics (2). With the addition of spinal x-rays, the understanding of spinal and whole-body biomechanics drastically changed.

••••

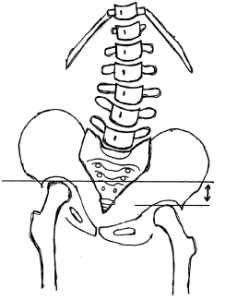

In 1916, Harvard Orthopedic Surgeon Robert W. Lovett, MD, published the third edition of his book Lateral Curvature of the Spine and Round Shoulders (3). This text has many examples of spinal radiographs, showing a biomechanical relationship between leg length, pelvic leveling, spinal scoliosis, and back pain.

••••

In 1927, American surgeon Dudley Joy Morton, MD, described a common foot problem that caused not only chronic foot pain and disability, but also affected the ankle, knee, pelvis and spine (4). Dr. Morton named the problem “Morton’s Toe.” Morton’s Toe is an anatomically short first metatarsal, giving the foot the appearance of an abnormally long second toe. The syndrome would cause abnormal stress at the first metatarsal-phalangeal joint, and the patient would compensate with altered foot and kinetic ambulatory function which could influence whole body mechanical functions, symptoms, and signs.

••••

The work of Morton became instrumental in the treatment of senator John F. Kennedy’s chronic low back pain by physician Janet Travell, MD, in 1955 (5). Then Lieutenant Kennedy’s notorious back problems were triggered during the legendary sinking of his boat PT-109 in the Pacific during WWII.

Kennedy never fully recovered from his back injuries. In 1954, Kennedy underwent a second attempted spinal fusion operation, and it did not go well. He nearly died, and his recovery took 8 months. The following year, Kennedy came under the care of myofascial pain expert Janet Travell, MD (6). After studying the work of Dr. Morton, Dr. Travell realized that all mechanical problems could cause compensatory contraction in the musculature system, leading to treatable findings called trigger points and a diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome.

Dr. Travell’s treatment of Senator Kennedy in 1955 was a resounding success, and it was headline news. When Kennedy was elected president of the United States (taking office in 1961), he chose Dr. Travell to be his personal White House Physician. Dr. Travell was the first female and civilian physician to hold this prestigious office (7, 8, 9).

When Dr. Travell first began treating Senator Kennedy’s mechanical problems and associated trigger points, he was non-ambulatory. His improvement was so impressive that Dr. Travell’s daughter wrote (6):

“Senator Kennedy received so much relief of pain from my mother’s medical treatments that he had ‘new hope for a life free from crutches if not from backache.’”

In 2003, James Bagg wrote [pertaining to Dr. Travell] (5):

“Jack Kennedy saw a great many physicians over the course of his short life, but one of them, according to his brother Bobby, enabled Jack to become President of the United States.”

The major revelation of Dr. Travell was that a toe problem would cause a foot problem which would cause a leg problem which would cause a spine problem. The resolution of the spinal complaints would require first rectifying the toe problem. Dr. Travell realized that both a toe problem and an anatomical short leg could both, independently, cause a spine problem. Dr. Travell realized that Senator Kennedy’s left leg was three-quarters of an inch shorter than that of his right leg.

••••

In 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Weaver A. Rush and Captain Howard A. Steiner of the X-Ray Department of the Regional Station Hospital of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, exposed upright lumbosacral x-rays on 1,000 soldiers (10). All study subjects suffered from low back pain. These authors noted:

-

- 23% of the soldiers had legs of equal length.

- 77% of the soldiers had unequal length of their legs.

These authors noted that the short leg was associated with a tilt of the pelvis and a scoliosis. They noted:

“[Whenever there is a pelvic tilt], there exists coincidentally a scoliosis of the lumbar spine.”

“Because this scoliosis, in all instances, compensates for the tilt of the pelvis, it is referred to by us as compensatory scoliosis.”

“The existence of this compensatory scoliosis in the presence of a tilted pelvis due to shortening of one or the other lower extremity is believed by us to have clinical significance.”

“It was a general consistent observation that the degree of scoliosis was proportionate to the degree of pelvic tilt. An individual who has a shortened leg will have to compensate completely if he intends to hold the upper portion of his body erect or in the midsagittal plane.”

“A consistent observation which has been made is that in those cases with a shortened leg there is a corresponding tilt of the pelvis and a compensatory scoliosis of the lumbar spine.”

Lieutenant Colonel Rush and Captain Steiner observed that leg length differences exceeding 5 mm were associated with the greatest low back pain or disability, and therefore 5 mm is labeled as being a “marked difference.” The authors stated:

“For this reason, it is our opinion that the existence of such a condition [a short leg exceeding 5 mm] is significant from the standpoint of symptomatology and disability.”

Dr. Travell measured Senator Kennedy’s left short leg at about three quarters of an inch, or about 18 mm.

Long Right Leg

Short Left Leg

••••

In 1980, physician, neurologist, and chiropractor Scott Haldeman wrote (11):

“If one leg is only a quarter of an inch shorter, the entire body can be tilted enough to cause pain throughout the skeletal system. So slight a difference can distort the entire skeleton, causing a ‘seesaw’ condition that pulls one shoulder down a full inch. This may never be recognized until the person is hurt in a fall or an accident.”

Dr. Haldeman is from the Department of Neurology, University of California, Irvine, California. The shoulder tilt magnification compensation to a pelvic unleveling may result in symptoms including neck pain and headaches. Once again, it is noted that the different regions of the spine are mechanically interconnected.

••••

In 1982, Richard Rothman, MD, PhD, and Frederick Simeone, MD, published the second edition of their book, The Spine (12). Dr. Rothman was a Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and Chief of Orthopedic Surgery at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia (d. 2018). Dr. Simeone was a Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Chief of Neurosurgery at the Pennsylvania Hospital, and Director of Neurosurgery at the Elliott Neurological Center of Pennsylvania Hospital.

Chapter 2 of Drs. Rothman’s and Simeone’s book is titled:

“Applied Anatomy of the Spine”

This chapter is written by Wesley Parke, PhD. In 1982, Dr. Parke was a Professor and Chairman of the Department of Anatomy at the University of South Dakota School of Medicine (d. 2005). In this chapter, Dr. Parke writes:

“Although the 23 or 24 individual motor segments must be considered in relation to spinal column as a whole, no congenital or acquired disorder of a single major component of a unit can exist without affecting first the functions of the other components of the same unit and then the functions of other levels of the spine.”

Dr. Parke is also noting that the entire spinal column is an integrated functioning unit.

••••

In 1987, an important addition to the understanding of modern integrative biomechanics was published by Finish physician Ora Friberg, MD (14). Dr. Friberg exposed standing radiographs of the pelvis and lumbar spine in 288 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain and in 366 asymptomatic controls. His findings showed that 73% of the subjects assessed had meaningful inequality of a lower limb (>5 mm shortness). The incidence of leg length inequality in low back pain patients was significantly higher than in asymptomatic controls (more than twice as much).

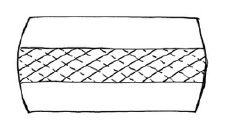

Importantly, Dr. Friberg emphasized the existence of counter-rotational stresses on the L5-S1 intervertebral disc in the presence of pelvic unleveling. The lumbar intervertebral discs are intolerant of chronic rotational stress because the nature of the crisscross annulus orientation essentially reduces mechanical integrity by half (15, 16). This concept would have a particular relevance to the chronic back problems and failed surgeries of former US President John Kennedy.

Crisscross Annular Fibers of the Intervertebral Disc

Axial View From Above

Midline

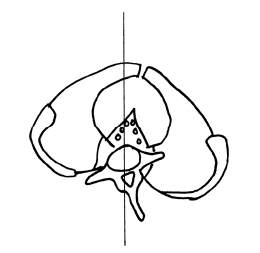

Short Left Leg Long Right Leg

The L5 spinous process will rotate to the right of midline, towards the side of the long leg (counterclockwise rotation).

The pubic symphysis and pelvis will also rotate to the right of midline, towards the side of the long leg (clockwise rotation).

This results in clinically meaningful counter-rotational stresses, primarily at the L5-S1 intervertebral disc. The consequences of these counter-rotational stresses at the L5 disc are accelerated disc degeneration and degradation, back pain, and sciatica.

••••

The concept of the entire spine functioning as a single integrated unit was nicely noted in the reference books (1987, #17; 1994, #18) written by rheumatologist John Bland, MD (d. 2008). Dr. Bland was a Professor of Medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine. His books were titled (17, 18):

Disorders of the Cervical Spine

In this book, Dr. Bland states:

“We tend to divide the examination of the spine into regions: cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine clinical studies.

This is a mistake.

The three units are closely interrelated structurally and functionally – a whole person with a whole spine.

The cervical spine may be symptomatic because of a thoracic or lumbar spine abnormality, and vice versa!

Sometimes treating a lumbar spine will relieve a cervical spine syndrome, or proper management of the cervical spine will relieve low backache.”

••••

In 1989, podiatrist Steven Subotnick, DPM, published his book titled Sports Medicine of the Lower Extremity (19). Dr. Subotnick was a Clinical Professor in the Departments of Biomechanics and Surgery at the California College of Podiatric Medicine, San Francisco, California. In his book, Dr. Subotnick notes that a pronation of the foot would result in a functionally short leg and a compensatory scoliosis. The scoliosis would affect the thoracic spine, the scapula, and result in a “compensation on the cervical area.”

Dr. Subotnick is another provider noting the integrated function between the foot, leg, pelvis, and entire spinal column.

••••

Recently, three reference texts have been published emphasizing the integrative nature of whole-body biomechanics:

-

- Energy Medicine, The Scientific Basis, by James Oschman, PhD, 2000 (20).

- Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists; by Thomas Myers, 2001 (21).

- Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, Katy Bowman, 2017 (22).

••••

In his 2000 book Energy Medicine, The Scientific Basis, James Oschman, PhD, notes that the entire body is mechanically interconnected via a connective tissue cytoskeletal matrix called the “tensegrity matrix.” He notes that mechanical providers of care, including chiropractors, solve health problems by attending to the quality of the tensegrity matrix.

Dr. Oschman notes that gravity is the most potent physical influence in any human life. He notes that tensegrity accounts for the fact that inflexibility or shortening in one tissue influences structure and movement in other tissues. He notes that the entire body is mechanically integrated and interconnected. An imbalance in one part of the body will affect the whole body. He states:

“The basic principle of gravitational biology is known to any child who plays with blocks. The center of gravity of each block must be vertically above the center of gravity of the one below, to have a stable, balanced arrangement. If the center of gravity of one block lies outside of the gravity line, stability is compromised.”

“There is only one stable, strain-free arrangement of the parts of the human body. Any variation from this orientation will require corresponding compensations in other parts of the support system. Misalignment of any part will affect the whole system.”

••••

In her 2017 book Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, biomechanist Katy Bowman agrees with Dr. Oschman, noting, “gravity is one force your body responds to constantly.” Ms. Bowman discusses the importance of understanding that humans experience loads 100% percent of the time while existing and functioning in a gravity environment.

Each tissue type responds differently to a load, yet “they are all connected, which means that a load you perceive as only happening in one part of your body is actually affecting all other parts of you, and affecting each part uniquely.” Once again, this is an understanding and statement that the whole body is mechanically integrated and interconnected. Ms. Bowman notes:

“Tissues that spend most of their time in a fixed position will adapt to that position by making alterations that are fairly permanent.”

“An under-moved area of the body will experience increases in the connective tissues.”

Ms. Bowman calls these “extra- connected” areas of the body “sticky spots.”

“On the cellular level, a sticky spot interferes with the transmission of forces throughout your tissues—mechanical signals that give cells context about loads placed upon them as well as position.”

When a joint has a sticky spot, “you compensate by moving other joints,” which may “come with a heavy dose of damage.” Areas just outside of the sticky spot “experience unnaturally high loads.”

“We need a tool to measure the loads, both on the whole body and on every body part. The tool I use is alignment.”

The “sticky spots” discussed by Ms. Bowman are an orthopedic component of the joint dysfunction that chiropractors describe as the subluxation. Common terminology for “sticky spots” within chiropractic education and clinical practice is “the fibrosis of repair.” Chiropractors are well aware that mechanical care given to a “sticky spot” will mechanically influence the entire system. Chiropractors are also aware that compensatory sticky spots also require mechanical care to enhance optimum and speedy resolution of clinical symptoms and signs.

••••

In 2004, clinicians from Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain, published a randomized control trial of mechanical based care for the management of whiplash injury (23). The aim of this clinical trial was to compare the results obtained with a manipulative protocol from the results obtained with a conventional physiotherapy treatment in patients suffering from whiplash injury. The authors used 380 acute whiplash injury (less than 3 months duration) subjects. All subjects were Quebec Task Force grades II and III:

GRADE II = neck complaint and musculoskeletal signs

GRADE III = neck complaint, musculoskeletal signs, and neurologic signs

The authors note:

“The goal of joint manipulation is to restore maximal, pain-free movement of the musculoskeletal system.”

“Our clinical experience with these patients [whiplash-injured] has demonstrated that manipulative treatment gives better results than conventional physiotherapy treatment.”

Manipulation is “effective in the management of whiplash injury.”

“Manipulative treatment is more effective in the management of whiplash injury than conventional physiotherapy treatment.”

An interesting observation by these authors is that optimal management of the neck and head complaints required that manipulation also had to be applied to mechanical findings in the lumbar spine and pelvis. Once again, this concept supports the concept that the spine is a single functioning unit: a whole person with a whole spine.

••••

In 2005, physician Steven Glassman, MD, and colleagues, published a study of 752 patients by looking at the effect of sagittal spinal balance on pain and health profiles (24). Using a plumb line, the authors assessed the magnitude of a forward head/neck complex and how it affected low back pain and disability. The authors noted:

“There was clear evidence of increased pain and decreased function as the magnitude of positive sagittal balance increased.”

Once again, it is clear that neck alignment has a significant influence on low back pain.

••••

In 2015, a group of physicians from New York, Chicago, Virginia, Oregon, Texas, California, Colorado, and the International Spine Study Group, published a study documenting the influence of the neck on the low back. Similar to the Glassman study above, the authors measured sagittal spinal balance using a plumb line.

The authors note that when the head is sagittally forward of the sacrum, the patient will have an increase in low back pain and disability. They also note that any improvement in cervical spinal sagittal alignment will proportionally improve low back pain and disability.

Putting It All Together

Patients present to chiropractors with a variety of musculoskeletal complaints, primarily back and neck pain (26). The information presented here shows that the entire body is mechanically integrated. It is standard for a chiropractor to evaluate the entire body mechanically, regardless as to the actual location of the patient’s primary complaint. Examining and treating the entire spine, including regions that may be asymptomatic, will as a rule enhance optimal clinical improvement. Such care will logically expand to include the feet, knees, and hips.

REFERENCES

- Fonder A; The Dental Physician; Medical-Dental Arts; 1985.

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1901/rontgen/facts/; accessed May 27, 2022.

- Lovett RW; Lateral Curvature of the Spine and Round Shoulders; third edition; P. Blakiston’s Son & Co.; Philadelphia; 1916.

- Morton DJ; METATARSUS ATAVICUS: The Identification of a Distinctive Type of Foot Disorder; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American; July 1, 1927; 9; No. 3; pp. 531-544.

- Bagg JE; The President’s Physician; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; 30; No. 1; pp. 1–2.

- Wilson V; Janet G. Travell, MD: A Daughter’s Recollection; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; Vol. 30; No. 1; pp. 8–12.

- Lacayo R; How Sick Was J.F.K.?; TIME; November 24, 2002.

- Altman LK, Purdum TS; In J.F.K. File, Hidden Illness, Pain and Pills; The New York Times; November 17, 2002.

- Dallek R; The Medical Ordeals of JFK; The Atlantic; December 2002.

- Rush WA, Steiner HA; A Study of Lower Extremity Length Inequality; American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy; November 1946; Vol. 56; No. 5; pp. 616-623.

- Haldeman S; Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractic; Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York; 1980.

- Rothman RH, Simeone FA; The Spine; second edition; WB Saunders Company; 1982.

- Parke WW; “Applied Anatomy of the Spine” chapter 2 in Rothman and Simeone; The Spine; second edition; WB Saunders Company; 1982.

- Friberg O; The statics of postural pelvic tilt scoliosis: A radiographic study on 288 consecutive chronic LBP patients; Clinical Biomechanics; November 1987; Vol. 2; No. 4; pp. 211-219.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume 3; The Trunk and

- the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second Edition; JB Lippincott Company; 1990.

- Bland J; Disorders of the Cervical Spine; WB Saunders Company; 1987; p. 84.

- Bland J; Disorders of the Cervical Spine; WB Saunders Company; 1994; p. 119.

- Subotnick SI; Sports Medicine of the Lower Extremity; Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

- Oschman J; Energy Medicine, The Scientific Basis; Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Meyers TW; Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists; Churchill Livingstone; 2001.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement; Propriometrics Press; 2017.

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Fernández-Carnero J, Palomeque del Cerro L; Miangolarra-Page JC; Manipulative Treatment vs. Conventional Physiotherapy Treatment in Whiplash Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders; 2004; Vol. 3; No. 2.

- Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F; The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity; Spine; September 15, 2005; Vol. 30; No. 18; pp. 2024-2029.

- Protopsaltis TS, Scheer JK, BS; Terran JS, and 12 others; How the Neck Affects the Back: Changes in Regional Cervical Sagittal Alignment Correlate to HRQOL Improvement in Adult Thoracolumbar Deformity Patients at 2-year Follow-up [HRQOL = health-related quality of life]; Journal of Neurosurgery Spine; August 2015; Vol. 23; No. 2; pp. 153–158.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.