Health science professors and clinicians often note that the most important aspect of healthcare education is anatomy. Anatomy holds the integration of pathology, complaint, and eventually treatment.

Diagnostic Concepts

Biology We May Not Know / Biology We May Have Forgotten

(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

-

- Compression on nerve roots and/or peripheral nerves does not cause pain. Rather, compression produces paresthesia [abnormal sensations such as tingling, numbness] and/or weakness and/or paralysis.

“Pressure on a nerve blocks conduction without causing stimulation.” [i.e., pain] (#4)

-

- Prolonged nerve compression will cause demyelination and scar/fibrosis. These changes may result in permanent nerve injury and permanent loss of nerve function.

- Repeated injury to a nerve will cause demyelination and scar/fibrosis. These changes may result in permanent nerve injury and permanent loss of nerve function.

- Pain afferents (nociceptors) have small (the smallest) diameter neuron fibers.

Mechanoreceptor afferents (proprioceptors) have large diameter (the largest) neuron fibers.

Nerve compression affects large diameter fibers (proprioceptors) before affecting small diameter (nociceptive/pain) fibers.

As such, nerve compression will adversely affect proprioception before it will adversely affect nociception.

-

- Compression of proprioceptive afferents results in the perception of numbness. This is a Key Point.

Clinical Protocols

How Do Clinicians Approach The Making Of A Diagnosis?

The clinical diagnosis is the clinician’s “best guess” as to what is wrong with a patient. When additional information is collected, the diagnosis may change or be updated. Establishing the initial “working diagnosis” involves these steps:

-

- Listen, record, detail, etc. the patient’s symptoms.

Obtain an adequate history to establish the cause/onset of the patient’s symptoms.

Perform examinations that confirm or rule-out suspected causations.

Order special tests, such as labs or imaging, to confirm or rule-out suspected diagnoses.

- Listen, record, detail, etc. the patient’s symptoms.

The Nervous System

There are several ways to categorize the nervous system. For this discussion a distinction is made between the cranial nerves and the spinal nerves.

Cranial refers to “head.” Classically, cranial nerves arise from the brain and/or from the brainstem. There is one noteworthy exception. This exception is the eleventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve XI, called the spinal accessory nerve. The spinal accessory nerve is fully formed in the neck from cervical roots C2-C3-C4-C5-C6. After it is formed it enters the skull through the foramen magnum but then quickly exits the skull through the jugular foramen to become the motor (movement) innervation to the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Although this nerve is referred to as being a cranial nerve, its origin is in the neck. It is fully formed in the neck. Technically, strictly, it is therefore a neck nerve, not a cranial nerve. Yet, after exiting the skull through the foramen magnum, it is known as cranial nerve XI, the spinal accessory nerve.

Officially, there are twelve cranial nerves. They are numbered with Roman numerals:

| Cranial Nerve | Name | Location | Basic Function |

| I | Olfactory | Brain | Smell |

| II | Optic | Brain | Vision |

| III | Oculomotor | Brainstem Mesencephalon | Eye Movement |

| IV | Trochlear | Brainstem Mesencephalon | Eye Movement |

| V | Trigeminal |

Brainstem Pons |

Facial Sensation Jaw Movement |

| VI | Abducens |

Brainstem Pons |

Eye Movement |

| VII | Facial |

Brainstem Pons |

Muscles of face expression (smile, frown) |

| VIII | Vestibulo-Cochlear |

Brainstem Pons |

Hearing Balance |

| IX | Glossopharyngeal |

Brainstem Medulla |

Throat Function |

| X | Vagus |

Brainstem Medulla |

Viscera Control (heart, lungs, gastrointestinal) |

| XI | Spinal Accessory | The Neck | Motor (movement) to trapezius and sternocleidomastoid |

| XII | Hypoglossal |

Brainstem Medulla |

Tongue Movement |

In contrast to cranial nerves, spinal nerves do not arise or exit from the skull. Spinal nerves arise from the spinal cord and exit from the spaces between the spinal vertebrae. For this discussion, the spinal nerve of greatest importance is the first spinal nerve, known as C1. C1 exists between the skull and the atlas (the first cervical vertebrae).

C1 is exclusively a sensory nerve. This means it only feel things (brings sensory electrical signals to the brain), and it does not control any muscles (movement).

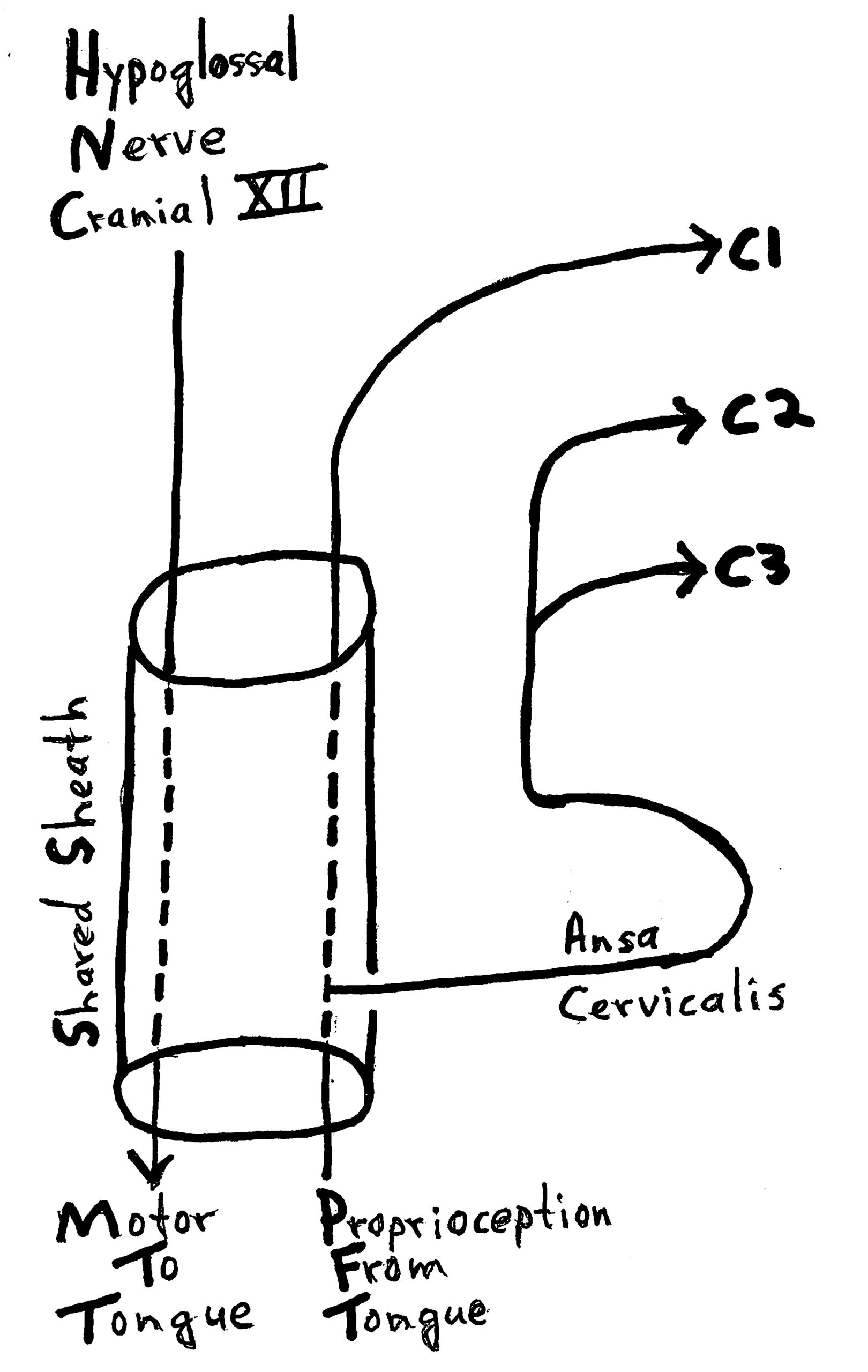

An important anatomical relationship is that the C1 nerve (a spinal nerve) travels with the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII), which is the motor nerve to the tongue. It is the nerve that controls tongue movement:

Additionally, when the tongue is moved to a specific location, we know (sense) where it is. This sense is known as proprioception. Importantly, tongue proprioception enters the spinal cord and brain via nerve roots C1, C2, and C3.

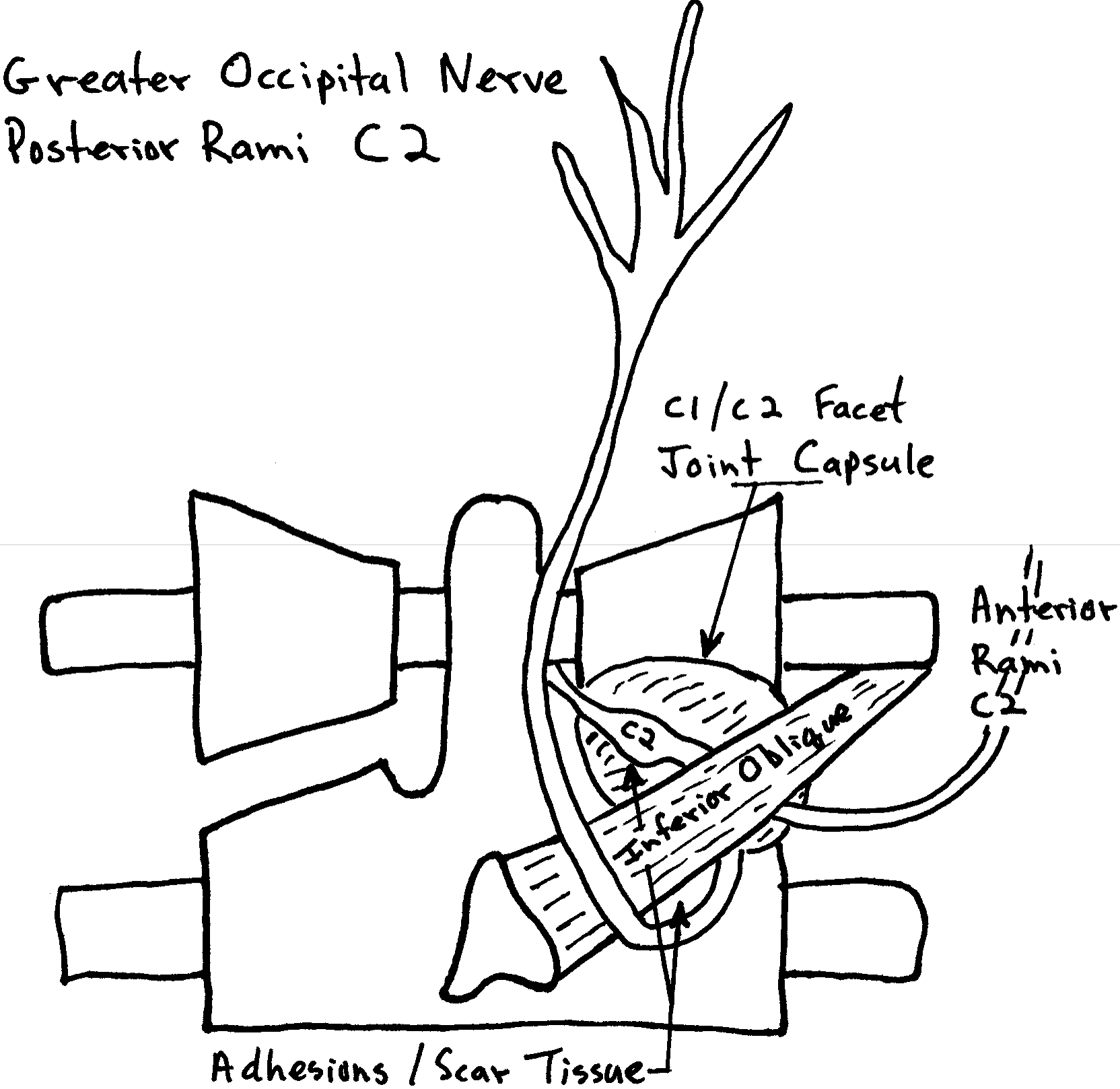

The take-home clinical message from all of this is that problems (irritations, inflammations, compressions) of nerve roots C1, C2, and/or C3 can result in tongue symptoms. These irritations, inflammations, compressions can be foraminal (nerve root) or peripheral (facet, at the capsule, or at the inferior oblique muscle).

It is counter-intuitive to think that mechanical problems in the neck can cause symptoms in the tongue because we are taught that the tongue is innervated by cranial nerve XII, the hypoglossal nerve, a cranial nerve. Yet, clinicians have observed the relationship between the neck and the tongue for some time. The scientific literature has reviewed the relationship a number of times beginning in 1980. The specifics of these relationships and the supportive scientific studies remain unknown by the vast majority of clinicians. Several of these studies are reviewed below.

The first noteworthy study was published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry in 1980, and titled (7):

Neck-Tongue Syndrome on Sudden Turning of the Head

The authors were from the Division of Neurology, The Prince Henry Hospital, Little Bay, and the School of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

These authors report on 4 cases of Neck-Tongue Syndrome from their clinical practice. All 4 patients were young, ages 15, 15, 17, and 26 years. Most of their symptoms initially started with a trauma and all were aggravated by neck rotation.

Symptoms included “sharp pain in the upper neck, occiput, or both areas together on sharp rotation of the neck, accompanied by numbness of the tongue on the same side and other [hand/arm] symptoms.” The authors state:

Neck-Tongue Syndrome is a “syndrome of unilateral upper nuchal or occipital pain, with or without numbness in these areas, accompanied by simultaneous ipsilateral numbness of the tongue is explicable by compression of the second cervical root in the atlantoaxial space on sharp rotation of the neck.”

The authors suggest that the site of irritation is the 2nd and/or 3rd cervical nerve root, which communicates with the 1st cervical nerve root. The 1st cervical nerve root travels with the Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial Nerve XII). They note that the 2nd cervical root is “particularly vulnerable to compression in its course between atlas and axis during excessive rotation of the neck.”

The authors note that the hypoglossal nerve is connected with a loop, the Ansa Cervicalis, with the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cervical roots. Hypoglossal proprioceptive afferent fibers enter the central nervous system by the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd cervical roots. They state:

Afferent fibers from the tongue “enter the central nervous system through the second cervical root and appear to have a proprioceptive function, so that it is surprising to find that sudden compression of these fibers in man gives rise to a sensation described as ‘numbness’ by the patients.”

“The mechanical disability of the upper cervical spine that induces compression of the second cervical root on sudden rotation of the neck almost certainly involves some degree of unilateral subluxation of the facets of the atlanto-axial joint.”

The neck-tongue syndrome is “attributable to instability of the upper cervical spine causing unilateral compression of the second (and possibly third) cervical root.”

The neck-tongue syndrome may be “caused by asymmetrical slipping of the facets, compressing a root but not the spinal cord.”

In brief, this study notes that:

-

- Tongue proprioceptive afferents travel in the sensory roots of C1, C2, and C3.

- Asymmetrical slipping of the upper cervical facets can compress/irritate the nerve roots, causing Neck-Tongue Syndrome.

••••••••••

The following year, 1981, Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, from the Division of Neurology, The Prince Henry Hospital, and the School of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia published an article in the same Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, titled (8):

An Anatomical Basis for the Neck-Tongue Syndrome

Dr. Bogduk dissected the C2 nerve roots and rami in five cadavers to explore the pathogenesis of Neck-Tongue Syndrome. Dr. Bogduk makes these points:

“The most likely cause of the simultaneous occurrence of suboccipital pain and ipsilateral numbness of the tongue is an abnormal subluxation of one lateral atlanto-axial joint with impaction of the C2 ventral ramus against the subluxated articular processes.”

It is argued that Neck-Tongue Syndrome symptoms are “due to compression of the second cervical nerve root in the atlanto-axial space; the numbness of the tongue was caused by compression of proprioceptive fibers coursing from the tongue through the ansa hypoglossi, the cervical plexus, and finally the second cervical dorsal root.”

“In the Neck-Tongue Syndrome, numbness of the tongue and suboccipital pain are triggered by rotation of the head. The site of pain and the precipitating maneuver clearly implicate an abnormality at upper cervical levels.”

It is “well established that proprioceptive fibers from the tongue do pass via the ansa hypoglossi to the C2 dorsal root.”

“A more satisfying explanation is that patients with Neck-Tongue Syndrome suffer a temporary abnormal subluxation of their lateral atlanto-axial joint which strains the joint capsule, thus causing pain.”

The tongue numbness “is explicable in terms of compression of the proprioceptive fibers.”

••••••••••

More recently (2016) an article from Georgetown University Hospital, Department of Neurology, was published in the journal Current Pain Headache Reports, and titled (9):

Neck-Tongue Syndrome

The authors note that the Neck-tongue syndrome is a “headache disorder often initiated by rapid axial rotation of the neck resulting in unilateral neck and/or occipital pain and transient ipsilateral tongue sensory disturbance.” They state:

“The anatomical basis of neck-tongue syndrome centers on the C1-C2 facet joint, C2 ventral ramus, and inferior oblique muscle in the atlanto-axial space.”

••••••••••

The most comprehensive review of the Neck Tongue Syndrome was published in the journal Cephalagia in 2018 (10). The authors were an international team of experts from the:

University of California, San Francisco

Boston Children’s Hospital

University of California, Davis

University of Newcastle, Australia

King’s College London, London

The article was titled:

Neck-Tongue syndrome: A Systematic Review

These authors undertook a systematic review of the literature to identify all reported cases in order to phenotype clinically the disorder and subsequently formulate clinical diagnostic criteria. They state that the Neck-Tongue syndrome is “characterized by brief attacks of neck or occipital pain, or both, brought out by abrupt head turning and accompanied by ipsilateral tongue symptoms.” The authors concluded:

“Neck-Tongue syndrome typically has pediatric or adolescent onset, suggesting that ligamentous laxity during growth and development may facilitate transient subluxation of the lateral atlantoaxial joint with sudden head turning.”

The authors also suggest that there may be a genetic predisposition in some individuals.

••••••••••

A text with a review chapter on the Neck-Tongue Syndrome suggests that the syndrome often becomes chronic unless effective treatment is administered (11). There are a number of studies that document the effectiveness of spinal manipulation for the syndrome, including these:

A study was published in the journal The Pain Clinic in 1986 and titled (12):

Treatment of Neck-Tongue Syndrome by Spinal Manipulation

The authors present three cases of neck-tongue syndrome that were successfully treated by rotational manipulation of the cervical spine. They also note that:

-

- There is often a history of head trauma before onset of symptoms.

- The symptoms commonly begin at a very young age, 8-14 years.

- The symptoms can be chronic, with documented cases lasting 18 years or longer.

CASE #1:

A 48-year old woman began having symptoms of neck tongue syndrome as a child, noting sharp right suboccipital pain with right head rotation.

“The patient was given a two-week course of daily manipulations directed towards mobilizing the upper and lower cervical spine on the right side. She tolerated the treatment quite well, and reported that she was symptom free after these treatments. She was reviewed at two weeks, three months, one year and two years after therapy and reported no further trouble. On each occasion, she demonstrated a full painless range of motion in the cervical spine with no numbness of the tongue.”

CASE #2:

A 28-year old woman had been suffering from left-sided neck-tongue syndrome for a year. The syndrome began one day following a whiplash injury, and physiotherapy had not improved her condition.

“The patient was given a two-week regimen of daily spinal manipulations directed towards mobilizing the upper cervical spine. The first two treatments caused an increase in neck discomfort, but by the end of the first week she was very much improved. After two weeks of treatment the tongue numbness was gone and could not be provoked.” She had no further episodes of tongue numbness at three months and six months after treatment.

CASE #3:

A 57-year old woman had been suffering from left-sided neck-tongue syndrome for years. There was no history of trauma.

“The patient was given a two-week course of daily spinal manipulations directed towards the upper cervical spine on the left side. She improved rapidly and was asymptomatic by the second week. She reported no further episodes of neck pain or tongue numbness when reviewed after two and six months.”

These authors conclude:

“We have been able to treat [neck-tongue syndrome] successfully with rotational manipulation of the cervical spine. We therefore suggest a short regimen of cervical manipulation for patients with neck-tongue syndrome before considering operative intervention.”

••••••••••

Several other published studies document the benefit of spinal manipulation in the treatment of neck-tongue syndrome (13, 14, 15). The most recent study on the topic showing a favorable response to chiropractic spinal manipulation was published in December 2018 in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

In this study, clinicians from the Chiropractic and Physiotherapy Department, New York Medical Group, Hong Kong, presented a case report, in which a 47-year-old man, who fulfilled the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for a diagnosis of neck–tongue syndrome, “was treated successfully with a chiropractic approach.”

This patient had been suffering for three months. Neither gabapentin [a drug used to treat neuralgia] nor diclofenac [a prescription NSAID] improved his symptoms.

The initial chiropractic treatment involved a regimen to mobilize the restricted joints and release a suspected impacted nerve. The treatment frequency was three treatments per week for a duration of four weeks (a total of twelve chiropractic visits). Following this approach, the patient’s “pain frequency and intensity had significantly decreased.”

After this, a second phase of treatment that was designed to relax hypertonic muscles and strengthen weak muscles began. The frequency and duration of this phase was also three times per week for four weeks.

Following the total of 24 chiropractic visits, there was “no further trouble.” The patient remained stable at a three-month follow-up.

The authors state:

“Neck-tongue syndrome is an under-recognized condition that can be debilitating for patients and challenging for the treating physicians.”

“The most likely cause of this clinical entity is a temporary subluxation of the lateral atlantoaxial joint with impaction of the C2 ventral ramus against the articular processes on head rotation.”

“Our patient above benefitted from cervical adjustment and this appears to support that cervical adjustment could be an effective approach for some cases of neck-tongue syndrome.”

“Chiropractic care for uncomplicated neck–tongue syndrome appears highly effective.”

••••••••••

There is strong evidence that spinal manipulation is an effective treatment for Neck Tongue Syndrome. At the very least, spinal manipulation should be the initial treatment of choice for this syndrome.

References

- Fontana F, in 1797; Cited by Meek WJ, Leaper WE; The effect of pressure on conductivity of nerve and muscle; American Journal of Physiology; 1911; 11; pp. 308-322. Found in The Upper Cervical Syndrome; Edited by Vernon H; Williams & Wilkins; 1988.

- Luttges MW, Gerren RA; Compression physiology: nerves and roots; In Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractic; Haldeman S; Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1980.

- Kelly M; Is pain due to pressure on nerves? Spinal tumors and intervertebral disc; Neurology; 1956; pp. 32-36.

- Vernon H, editor; The Upper Cervical Syndrome; Williams & Wilkins; 1988.

- Nolte J; The Human Brain; Mosby Year Book; 1993.

- Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T; Principles of Neural Science; McGraw-Hill; 2000.

- Lance JW; Anthony M; Neck-Tongue Syndrome on Sudden Turning of the Head; Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry; February 1980; Vol. 43; No. 2; pp. 97-101.

- Bogduk N; An Anatomical Basis for the Neck-Tongue Syndrome; Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry; March 1981; Vol. 44; No. 3; pp. 202-208.

- Hu N, Dougherty C; Neck-Tongue Syndrome; Current Pain Headache Reports; April 2016; Vol. 20; No. 4; pp. 27.

- Gelfand AA, Johnson H, Lenaerts ME, Litwin JR, De Mesa C, Bogduk N, Goadsby PJ: Neck-Tongue syndrome: A systematic review; Cephalalgia; February 2018; Vol. 38; No. 3; pp. 374-382.

- Terrett AGJ; Neck-tongue syndrome and spinal manipulative therapy, In: Vernon H ed. Upper Cervical Syndrome: Chiropractic Diagnosis And Treatment; Williams and Wilkins; 1988; pp. 223-229.

- Cassidy JD, Diakow PRP, De Korompay VL, Munkacsi I, Yong-Hing K; Treatment of Neck-Tongue Syndrome by Spinal Manipulation; The Pain Clinic; Vol. 1; No. 1; 1986; pp. 41-46.

- Borody C; Neck-tongue syndrome; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; 2004; Vol. 27; No. 5; pp. e8.

- Niethamer L, Myers R. Manual therapy and exercise for a patient with neck-tongue syndrome: A case report; Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy; 2016; Vol. 46; pp. 217–224.

- Roberts C; Chiropractic Management of a Patient with Neck-Tongue Syndrome: A Case Report; Journal of Chiropractic Medicine; December 2016; Vol. 15; pp. 321-324.

- Chu ECP, Lin AFC; Neck–Tongue Syndrome; BMJ Case Reports; December 4, 2018; Vol. 11; No. 1; e227483.

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.