Pain is a huge problem in America. Approximately half of adults in America suffer from chronic pain (1).

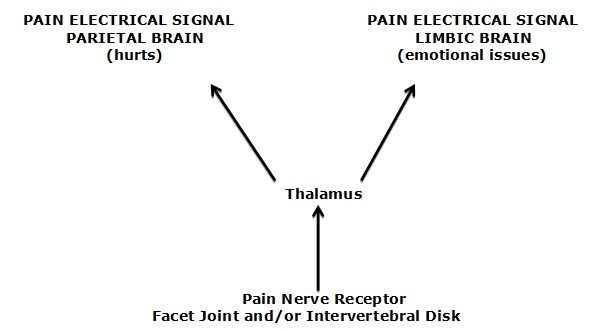

Classic, uncomplicated pain starts in peripheral tissues, initiating an electrical signal that travels along the pain nerve (nociceptor) to the brain. Pain is an electrical signal interpreted by the brain.

The primary reason for the initiation of pain from the peripheral tissue is inflammation (2). Consequently, minimizing and/or treating peripheral inflammation is an important approach in pain management.

The primary source of chronic lower back pain is the annulus of the disk (3, 4). The primary source of chronic neck pain is the facet joint capsule (5, 6).

It is well understood and accepted that the pain electrical signal, on its pathway from the inflamed peripheral tissue to the (parietal) brain, also communicates with the limbic (emotional) brain. Consequently, in addition to hurting, pain also causes suffering and emotional problems, such as depression (7):

The observations that chronic pain patients also have abnormal psychological profiles have led to much controversy, centering around two questions. These questions are essentially similar to the age-old question:

What comes first, the chicken or the egg?

The questions are:

Does an abnormal psychological profile cause chronic pain?

OR

Does chronic pain cause an abnormal psychological profile?

An answer to this question was provided, using primary research and gold-standard protocols by a team of well-respected researchers. Their study appeared in the journal Pain in 1997, and was titled (8):

Resolution of Psychological Distress of Whiplash Patients

Following Treatment by Radiofrequency Neurotomy:

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

The authors sought to evaluate:

-

- The psychological model of chronic neck pain: whether psychological distress precedes and causes the chronic pain

or

-

- The medical model : whether the psychological distress is a consequence of chronic pain.

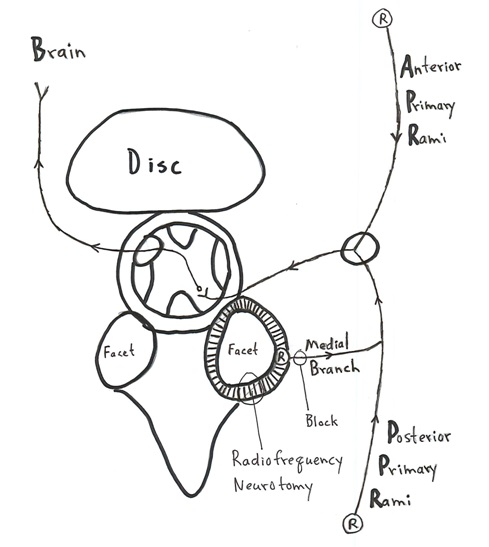

The study used 17 neck pain subjects who were assessed and treated using a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled approach. All subjects were found to have a single painful zygapophysial joint, diagnosed by double-blind, placebo-controlled cervical medial branch blocks (see drawing).

Nine of the study subjects were treated with radiofrequency neurotomy (treatment group). Eight of the subjects (the placebo group) were similarly treated, but the machine was not turned on.

The facet joint has nociceptors “R” which are connected to the brain through the medial branches of the posterior primary rami .

Diagnostic anesthetic blocking of the medial branch of the posterior primary rami eliminated the neck pain in all 17 study subjects, indicating the facet is the source of their neck pain.

Radiofrequency neurotomy of the facet joint capsules coagulates the neurofiliment proteins, eliminating the pain in all such treated subjects.

The authors evaluated these subjects using three measurement tools:

-

- The SCL-90-R psychological profile

- The McGill Pain Questionnaire

- The visual analogue pain scale

The authors state the following:

-

- The SCL-90-R psychological symptom checklist is a suitable tool to measure psychological distress in patients with chronic pain.

- There is little evidence of useful clinical improvement following psychological treatment in chronic pain patients. Even when psychological improvement has been demonstrated, it has not been associated with a clinically useful degree of pain reduction, let alone complete relief of pain. At best, psychological interventions enable patients to return to work in spite of their pain.

- Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy is a 3 hour long, local anesthetic, operative neuroablative procedure which provides long-term, complete pain relief by coagulating the nerves that innervate the painful zygapophysial joint. This neurosurgical procedure has been validated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

- Radiofrequency neurotomy does not effect a permanent cure. It provides long-term pain relief, from months to years. Recurrence of the pain is natural as the coagulated nerve heals.

Three months after the intervention, all of the treatment group subjects were pain free. Importantly, they all also exhibited resolution of their psychological distress. In contrast, the placebo group did not have lessened pain, and their psychological distress remained unchanged. The authors stated:

“The association between complete relief of pain and resolution of psychological distress was very strong.”

With time (months), as expected, as the treated nerve healed, the subject’s pain returned. With the return of their pain, their psychological distress also returned. A second radiofrequency neurotomy on these subjects once again relieved their pain and their psychological distress. The authors state:

“As their original pain recurred, so did their psychological distress, but when successful active neurosurgical treatment again achieved pain relief, the psychological distress was again resolved.”

“None of the patients received any formal psychological therapy. The only intervention was the operative procedure. Therefore, such changes in the psychological profile as were observed can only be ascribed to the neurosurgical intervention.”

The results of this study clearly refute the psychological model , which would have predicted that because no psychological intervention was administered, no patient should have exhibited improvement in either their pain or psychological status. Yet, the treated subjects exhibited complete resolution of psychological distress. The authors state:

“This result calls into question the present nihilism about chronic pain, that proclaims medical therapy alone to be ineffectual, and psychological co-therapy to be imperative.”

These authors concluded:

“All patients who obtained complete pain relief exhibited resolution of their pre-operative psychological distress.”

“In contrast, all but one of the patients whose pain remained unrelieved continued to suffer from psychological distress.”

“Because psychological distress resolved following a neurosurgical treatment which completely relieved pain, without psychological co-therapy, it is concluded that the psychological distress exhibited by these patients was a consequence of the chronic somatic pain.”

There is no doubt or argument that chiropractic care is both scientific and helps the majority of people with spine pain syndromes. As an example, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was a Professor Emeritus of Orthopedics and director of the Low-Back Pain Clinic at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada. In 1985 he stated (9):

“Spinal manipulation, one of the oldest forms of therapy for back pain, has mostly been practiced outside of the medical profession.”

“Over the past decade, there has been an escalation of clinical and basic science research on manipulative therapy, which has shown that there is a scientific basis for the treatment of back pain by manipulation.”

“Most family practitioners have neither the time nor inclination to master the art of manipulation and will wish to refer their patients to a skilled practitioner of this therapy.”

More recently Jon Adams, PhD, and colleagues used the National Health Interview Survey to determine the present state of chiropractic in the United States. The aim of their study was to investigate the lifetime and 12-month prevalence, patterns, and predictors of chiropractic utilization in the US general population. Their findings were published in the journal Spine in December 2017 (10).

The authors note that chiropractors use manual therapy to treat musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. They state:

“Back pain (63.0%) and neck pain (30.2%) were the most prevalent health problems for chiropractic consultations and the majority of users reported chiropractic helping a great deal with their health problem and improving overall health or well-being.”

“A substantial proportion of US adults utilized chiropractic services during the past 12 months and reported associated positive outcomes for overall well-being and/or specific health problems for which concurrent conventional care was common.”

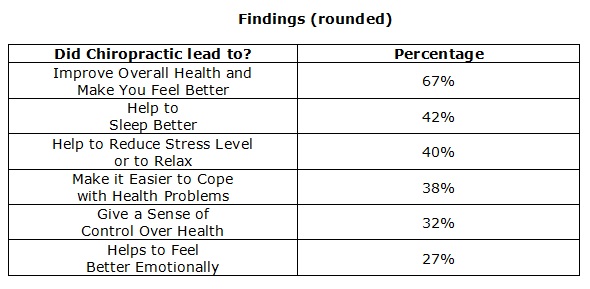

“Many respondents reported positive outcomes of chiropractic utilization agreeing that such care had helped them to improve overall health and make them feel better (66.9%), to sleep better (41.9%), and to reduce stress or to relax (40.2%).”

“Back pain or back problems (63.2%) and neck pain or neck problems (30.2%) were by far the top specific health problems for which people consulted a chiropractor in the past 12 months, followed by joint pain/stiffness (13.6%) and other pain conditions. Around two in three users (64.5%) reported that chiropractic had helped a great deal to address these health problems.”

“Our analyses show that, among the US adult population, spinal pain and problems – specifically for back pain and neck pain – have positive associations with the use of chiropractic.”

“The most common complaints encountered by a chiropractor are back pain and neck pain and is in line with systematic reviews identifying emerging evidence on the efficacy of chiropractic for back pain and neck pain.”

“Chiropractic services are an important component of the healthcare provision for patients affected by musculoskeletal disorders (especially for back pain and neck pain) and/or for maintaining their overall well-being.”

Importantly, when chiropractors treated their patients for back and/or neck pain complaints, they also noted improvements in other aspects of their well-being that could be attributed to the limbic brain:

Perhaps, as noted above (7), reducing the pain signal to the brain also reduced an adverse signal to the limbic brain.

••••••••••

Very recently (May-June 2018), a case study was published in the Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care , titled (11):

Long-Term Relief from Tension-Type Headache

and Major Depression Following Chiropractic Treatment

This article presented a case report of a 44-year-old woman who experienced long-term relief from tension-type headaches and major depression following chiropractic treatment. The report highlights the rewarding outcomes from spinal adjustments in certain neuropsychiatric disorders.

Case Report:

-

- This 44-year-old female suffered with tension-type headache, daily, of 2 years duration.

- Her pain was disabling, going across the forehead to her nuchal area and right shoulder.

- She was dependent upon pharmacology. She could not maintain her daily activities without acetaminophen and aspirin.

- Blood tests, brain MRI, and cervical x-rays were all unremarkable.

- Treatment with physiotherapy, acupuncture, traditional Chinese therapy, and other drugs all failed to help or to change her headache pattern.

- She began experiencing episodes of extreme low moods, characterized by feelings of overwhelming sadness.

- She was referred to the psychiatry services and was diagnosed with a major depressive disorder.

- Six months of various drug treatments for depression failed to help her.

- Both her disabling headache and her severe depression impaired her ability to perform her job and engage in regular activities.

- Because of the stresses of her health and finances, she had recurrent thoughts of death and suicide.

Chiropractic Evaluation:

-

- Her headache intensity was graded as 6–8/10 on the numeric pain rating scale.

- She had decreased spinal ranges of motion in the lower cervical and upper thoracic segments.

- She had spasm of the sternocleidomastoid, suboccipital and cervical paraspinal muscles.

- The neurological findings of both upper extremities were unremarkable.

Chiropractic Treatment:

-

- The chiropractic strategy was to stretch and relax the spastic muscles, restore motion in the respective segments, and to rehabilitate sensorimotor integration with diversified spinal manipulation.

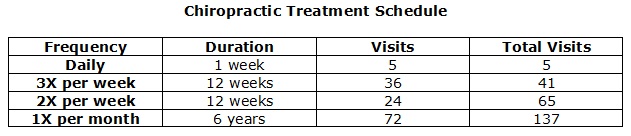

- The chiropractic treatment schedule is summarized in the following chart. Importantly, the authors waited six years after the resolution of signs and symptoms to publish their results. This allowed them to assess the long-term stability of their clinical outcomes. During this six-year period the patient agreed to monthly maintenance chiropractic care.

Clinical Outcomes:

-

- After 3 months (41 chiropractic visits), the patient regained confidence in her health and started reducing the dose of medications.

- At 3 months, she rated her headache as 3–5/10 on the pain scale.

- After 6 months (65 chiropractic visits) “all of her symptoms disappeared, and she was able to discontinue all medications.”

- “Having enjoyed headache free and mood stability over the past 6 years, the patient continued maintenance care on a monthly basis.”

These authors state:

“Chronic pain and depression can influence one another through complex webs of connections.”

“Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk are commonly found in patients with painful physical symptoms such as chronic headache, backache, or joint pain.”

Chiropractic adjustments “may lead to some therapeutic outcomes in certain neuropsychiatric disorders.”

“Chiropractic care is a way to reduce the frequency of pain, and the duration and intensity of headaches.”

“Better pain control from chiropractic care might be further beneficial for reducing depressive mood.”

In this case study, the clinical goal of the chiropractors was to help their patient with her chronic debilitating headaches. The purpose of their publication is to share adjunct benefits of successful resolution of chronic headache from chiropractic care.

SUMMARY

Chiropractors primarily treat musculoskeletal pain syndromes. Studies continue to show that for treating musculoskeletal pain syndromes, chiropractic care is effective, safe, and cost effective. Patient satisfaction levels with their chiropractic care is extremely high (10). Chiropractic care is especially helpful in chronic pain syndromes (12, 13, 14, 9).

Chronic musculoskeletal syndromes have an emotional, limbic component that can manifest as psychological signs and symptoms as well as an abnormal psychological profile. Improvements in other aspects of health and well being while receiving chiropractic care for musculoskeletal pain is a welcome addition.

REFERENCES

- Foreman J; A Nation in Pain, Healing Our Biggest Health Problem; Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Omoigui S; The biochemical origin of pain: The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; pp. 1169–1178.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; Vol. 22; No. 2; April 1991; pp. 181-187.

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, D’Aprile P, Muto M; Spine Pain; European Journal of Radiology; May 2015; Vol. 84; pp. 746–756.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C; On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks; Pain. August 1993; Vol. 54; No. 2; pp. 213-217.

- Bogduk N; On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash; Spine; December 2011; Vol. 36; No. 25S; pp. S194–S199.

- Blair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K; Depression and Pain Comorbidity, A Literature Review; Archives of Internal Medicine; November 10, 2003; Vol. 163; No. 24; pp. 2422-2445.

- Wallis BJ, Lord SM, Bogduk N; Resolution of Psychological Distress of Whiplash Patients Following Treatment by Radiofrequency Neurotomy: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial; Pain; October 1997; Vol. 73; No. 1; pp. 15-22.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Chu ECP, Ng M; Long-Term Relief from Tension-Type Headache and Major Depression Following Chiropractic Treatment; Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care May-June 2018; Vol. 7; No. 3; pp. 629-631.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; Volume 300, June 2, 1990; pp. 1431-1437.

- …; Chiropractors and Low Back Pain; Lancet; July 28, 1990; p. 220.

- Woodward MN, Cook JCH, Gargan MF, Bannister GC; Chiropractic treatment of chronic ‘whiplash’ injuries; Injury; November 1996; Vol. 27; No. 9; pp. 643-645.

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.