The Foot, The Leg, The Pelvis, And Back Pain

Foot problems are a common cause of low back pain.

Inequality of the length of the legs is a common cause of low back pain.

A pelvis that is not level is a common cause of low back pain.

The biomechanics of the low back are intimately linked to the biomechanics of the foot, leg, and pelvis. The actual tissue source for low back pain can be the intervertebral disc, the facet joints, the muscles, the ligaments, the nerves, or a combination of these. Individuals with back pain and their doctors may be tempted to only treat these tissues in the back, yet often the stresses in these tissues are caused by biomechanical problems in the feet, legs or pelvis. Failure to assess and manage biomechanical problems of the foot, leg and/or pelvis often results in poor or incomplete clinical outcomes in patients with back pain. The successful mechanical management of low back pain often requires the assessment and management of biomechanical problems of the lower extremity and pelvis because they are linked through the kinetic chain of stance, posture and ambulation.

•••••

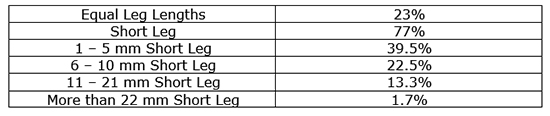

In 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Weaver A. Rush and Captain Howard A. Steiner of the X-ray Department of the Regional Station Hospital of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, meticulously exposed upright lumbosacral x-rays on 1,000 soldiers for the specific purpose of measuring differences in their leg lengths and to determine if inequality of leg length was a factor in the incidence of back pain. They published their results in the American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy in an article titled (1):

A Study of Lower Extremity Length Inequality

In this study, the authors constructed a spinal fixation and stabilization device to ensure the accuracy of upright measurements of leg length and their effects on spinal alignment. The 1,000 soldiers in this study were “consecutive, non-selected cases who were sent to the roentgen department because of a low back complaint.” By using their meticulous methodology of measurement, these authors concluded, “it is possible to accurately measure differences in lower extremity lengths as manifested by a difference in the heights of the femoral heads.” The greatest difference in leg length measured was 44 mm, or about 1.75 inches. The authors made the following observations:

23% of the soldiers had legs of equal length.

77% of the soldiers had unequal length of their legs.

The incidence of limb shortness was nearly equal between the left and right, and the average shortening was slightly more than 7 mm.

Importantly, concerning spinal biomechanical function, these authors noted that the short leg was associated with a tilt of the pelvis and a scoliosis. The authors noted:

The roentgenograms were made in the upright position with the use of the stabilization device. Whenever there is a pelvic tilt, “there exists coincidentally a scoliosis of the lumbar spine.”

“Because this scoliosis, in all instances, compensates for the tilt of the pelvis, it is referred to by us as compensatory scoliosis.”

“The existence of this compensatory scoliosis in the presence of a tilted pelvis due to shortening of one or the other lower extremity is believed by us to have clinical significance and, furthermore, it is our opinion that the existence of any such condition cannot be determined with any degree of accuracy on gross physical examination.”

“Furthermore, it becomes immediately apparent that the making of roentgenograms of the lumbosacral spine in the recumbent position, as is frequently done, completely prevents the discovery of such pathology as this.”

“It was a general consistent observation that the degree of scoliosis was proportionate to the degree of pelvic tilt. An individual who has a shortened leg will have to compensate completely if he intends to hold the upper portion of his body erect or in the midsagittal plane.”

“A consistent observation which has been made is that in those cases with a shortened leg there is a corresponding tilt of the pelvis and a compensatory scoliosis of the lumbar spine.”

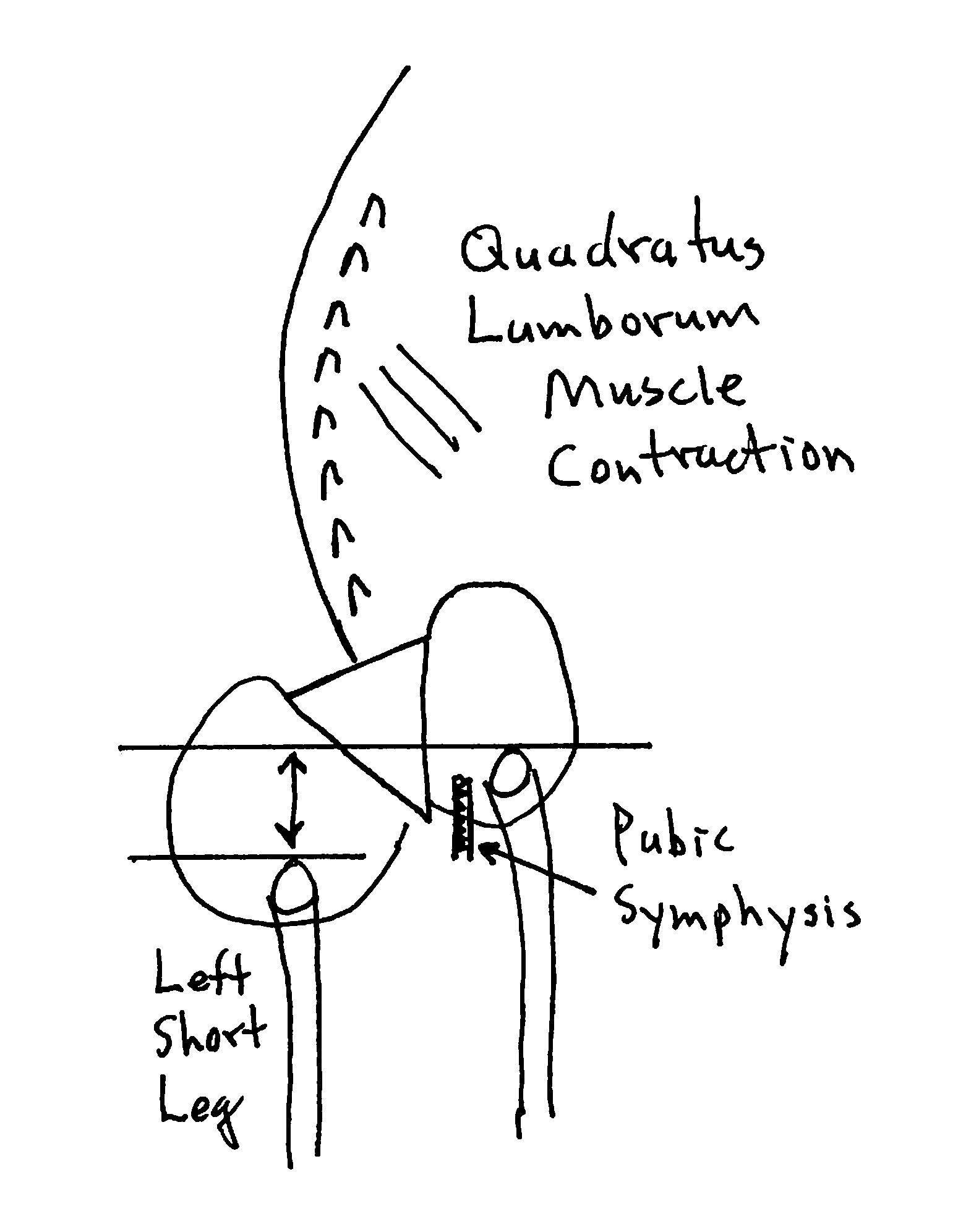

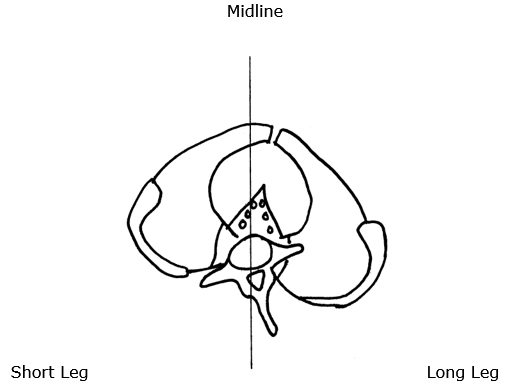

Posterior to Anterior View From Behind

- The sacrum is lower on the side of the short leg (left in this drawing).

- The spinal column initially tilts towards the short leg, then compensates back to the midline as a consequence of contraction of the quadratus lumborum muscle.

- The lumbar spinous processes (posterior) rotate towards the long leg. The pubic symphysis (anterior) also rotates towards the long leg. The consequent counter-rotational forces abnormally stress the L5 intervertebral disc.

•••••

Leg length differences exceeding 5 mm were associated with the greatest low back pain or disability, and therefore 5 mm is labeled as being a “marked difference.” The authors stated:

“For this reason, it is our opinion that the existence of such a condition [a short leg exceeding 5 mm] is significant from the standpoint of symptomatology and disability.”

•••••

Our nation and much of the world recently celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of former US president John F. Kennedy (May 29, 1917). President Kennedy suffered from a notorious bad back. His back problems significantly worsened in August of 1943 during the sinking of his boat PT-109 in the Pacific during WWII. Injured (he was awarded the Purple Heart for the event) Kennedy twice swam for miles in the Pacific Ocean, towing an injured crewmember with a life jacket strap in his teeth. Kennedy’s back problems never fully recovered.

In 1954, then Senator Kennedy underwent an attempted spinal fusion operation, and it went badly; it was his second spinal surgery for his persistent low back pain. He nearly died, and his recovery took 8 months. The following year, Kennedy came under the care of myofascial pain expert Janet Travell, MD. When Kennedy was elected president of the United States (taking office in 1961), he chose Dr. Travell to be his personal White House Physician. Dr. Travell was the first female physician to hold this prestigious office (2, 3, 4). President Kennedy considered Dr. Travell to be a medical genius (5).

Dr. Janet Travell received her MD degree from the Cornell University Medical College in New York City, where she graduated at the head of her class; she was also the first female to graduate from Cornell. For three decades she practiced cardiology while teaching pharmacology at Cornell.

By 1952, Dr. Travell’s clinical interest and practice had moved away from cardiology and she became a specialist in musculoskeletal pain syndromes. With her growing positive reputation and expertise, Senator Kennedy’s orthopedic surgeon asked Dr. Travell to look at his patient’s chronic, disabling back problems (5).

When Dr. Travell first saw Senator Kennedy in May of 1955, he was non-ambulatory. He had suffered from 2 devastating spinal surgeries, yet he continued to suffer from debilitating back spasm and left leg pain. Things were so bad that Senator Kennedy was “questioning his ability to continue his political career.”(6) Dr. Travell treated Senator Kennedy. His improvement was so impressive that Dr. Travell’s daughter wrote (5):

“Senator Kennedy received so much relief of pain from my mother’s medical treatments that he had ‘new hope for a life free from crutches if not from backache’.”

In 2003, James Bagg wrote this, pertaining to Dr. Travell (6):

“Jack Kennedy saw a great many physicians over the course of his short life, but one of them, according to his brother Bobby, enabled Jack to become President of the United States.”

Following Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and after continuing to work as White House Physician for then President Lyndon Johnson for a few years, Dr. Travell moved on to George Washington University School of Medicine. At George Washington University she teamed up with ex-Air Force Flight Surgeon David G. Simons, MD, and together they wrote the three most authoritative texts pertaining to myofascial pain syndromes ever compiled (years 1983, 1992, 1999) (references 7, 8, 9):

Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction:

The Trigger Point Manual

•••

Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction:

The Trigger Point Manual:

THE LOWER EXTREMITIES

•••

Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction

The Trigger Point Manual:

Volume 1, Upper Half of Body

In these books, Drs. Travell and Simons discuss difficult cases caused by structural inadequacies, the most common of which were:

- A difference in the length of the lower limbs.

- A long second metatarsal or a short first metatarsal (Morton’s Toe).

It has been documented since 1946 that about 75% of people have legs of unequal lengths, and that about a third of people have leg length differences that can perpetuate trigger points (1). As a rule, the sacrum is lower on the side of the short leg (see drawing). The spinal column initially tilts towards the short leg, then compensates back to the midline as a consequence of chronic contraction of the quadratus lumborum muscle. According to Dr. Travell, the resulting trigger points in the quadratus lumborum muscle is a very common but frequently overlooked cause of chronic low back pain (8).

Dr. Travell “discovered that one of [Senator] Kennedy’s legs was shorter than the other and made heel lifts for all of his left shoes to counter that additional source of stress on his back.” “Dr. Travell had a workbench in her office and made lifts for both patients and family members. ‘One of the first things I did for him [Kennedy] was to institute a heel liftóa correction for the difference in leg length’.”(6)

•••••

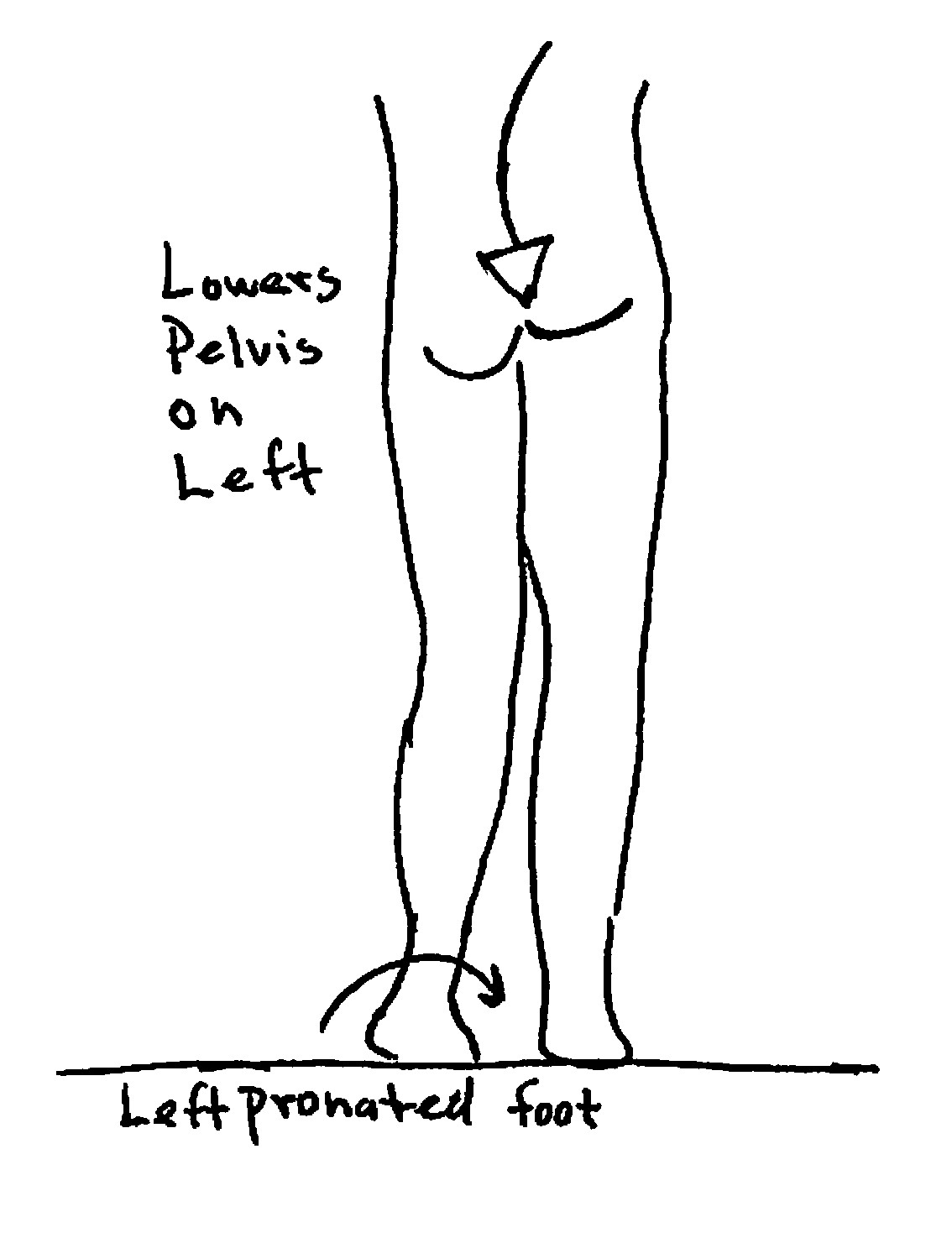

The Morton’s Toe was described by American orthopedic surgeon Dudley J. Morton, MD, from Yale, in 1927 (10). Dr. Morton noted that people suffered from a variety of chronic pain syndromes when they had a long second metatarsal or a short first metatarsal (which he termed Morton’s Toe). This common anatomic variant would alter the normal weight-bearing function of the foot, causing a compensatory pronation. Travell observed that this would lower the pelvis on that side, creating the identical trigger points as a leg length inequality.

Dr. Travell notes that the solution is a proper heel lift if the leg was anatomically short, and a shoe orthotic that re-establishes foot mechanics and weight-bearing, usually by correcting the pronation. She notes that other causes of foot pronation can and should be similarly addressed with an orthotic.

This concept of a pronated foot lowering the pelvis on the same side, altering lumbar spine biomechanics has been confirmed in more recent publications, including sports medicine reference books authored by podiatrists (11).

•••••

Another factor for the increased incidence of low back pain in individuals with an anatomical short leg and/or a foot pronation is that such factors not only cause myofascial pain syndrome in the quadratus lumborum muscle, they also cause counter-rotational stress at the L5-S1 intervertebral disc. This phenomenon was best described by Ora Friberg, MD, from Finland. Dr. Friberg published his findings in 1987 in the journal Clinical Biomechanics, titled (12):

The Statics of Postural Pelvic Tilt Scoliosis;

A Radiographic Study on 288 Consecutive Chronic LBP Patients

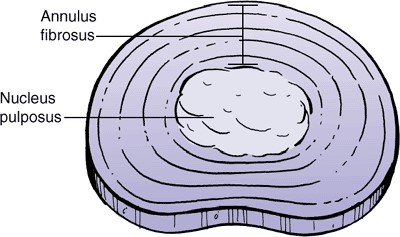

BACKGROUND ANATOMY

The intervertebral disc has two components. The center of the disc is called the Nucleus Pulposus, or simply nucleus. The nucleus is mostly water and functions as a ball bearing, allowing the vertebrae to bend and twist.

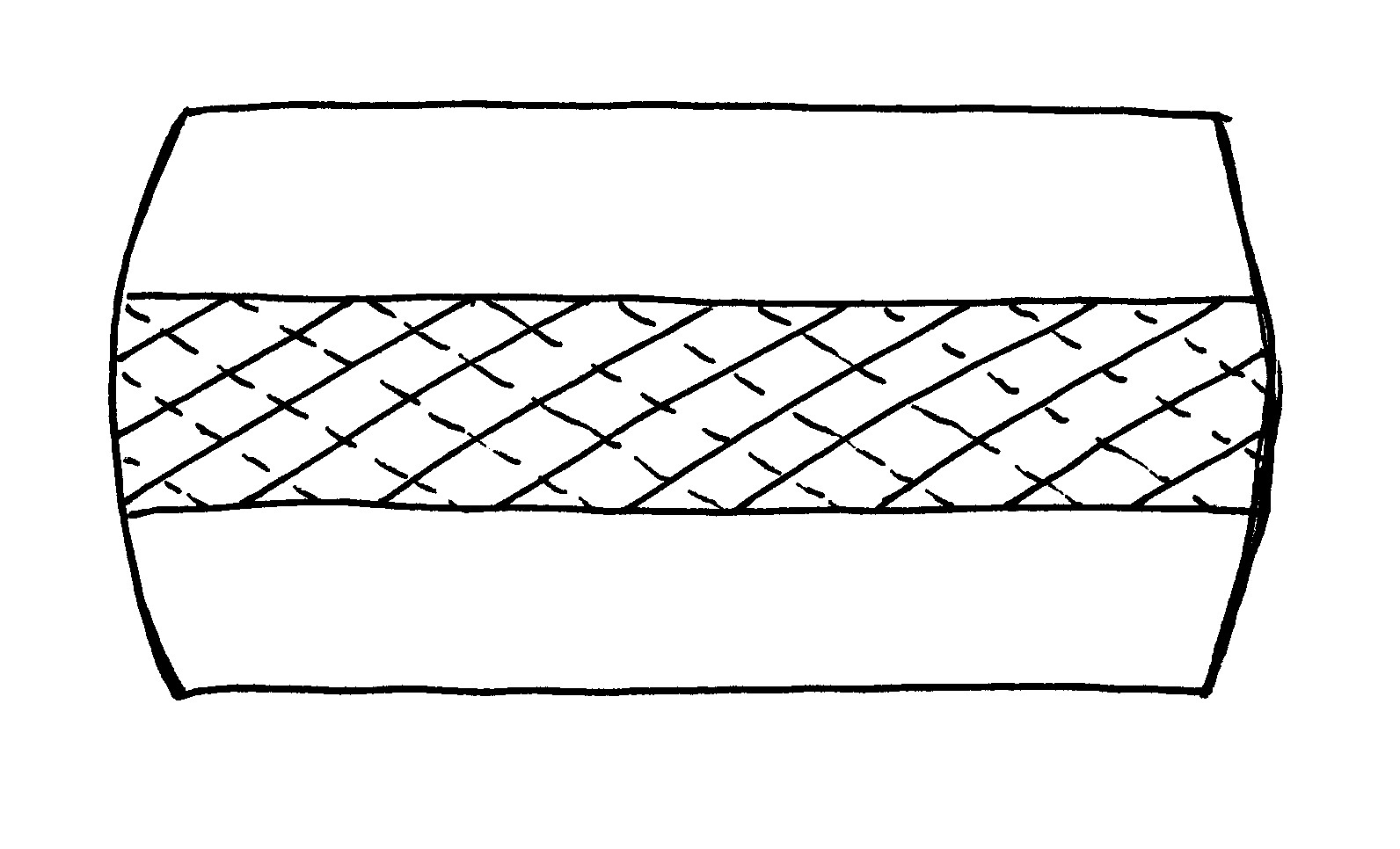

The nucleus is surrounded by tough outer fibers called the Annulus Fibrosis, or simply annulus.

The fibers of the annulus are arranged in layers, and each layer is crossed in opposite directions. During chronic rotational stress on the disc, half of the annular fibers become tense, and the other half become lax. Rotational stress applied to the annulus is resisted by only half of the annular fibers. The disc is operating at only half strength during rotationally applied stress, increasing its vulnerability to injury and degenerative disease. The disc is intolerant to chronic rotational stress (13).

Crossed Annular Fibers of the Intervertebral Disc

•••

In this study by Friberg, standing radiographs of the pelvis and lumbar spine in 288 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain and in 366 asymptomatic controls were exposed. His findings showed that 73% of the subjects assessed had meaningful inequality of a lower limb (>5 mm shortness). The incidence of leg length inequality in LBP patients was significantly higher than in asymptomatic controls (more than twice as much).

Friberg’s biomechanical findings were consistent with the findings of Rush/Steiner above. Friberg emphasized the counter-rotational stresses on the L5-S1 disc:

Axial View From Above

-

- The L5 spinous process has rotated to the right of midline, towards the side of the long leg. This causes a counterclockwise rotation of the L5 vertebrae and a counterclockwise rotation of the L5-S1 intervertebral disc.

- The pubic symphysis and pelvis has rotated to the right of midline, also towards the side of the long leg. Because the pubic symphysis is in the anterior, this causes a clockwise rotation of the pelvis and sacrum, and a clockwise rotation of the L5-S1 intervertebral disc.

- These “significant” counter-rotational stresses primarily affect the L5-S1 intervertebral disc. The consequences of these counter-rotational stresses at L5 are accelerated disc degeneration and degradation, back pain and sciatica.

•••••

Over the decades, numerous studies have continued to document the relationship between foot pronation, anatomical short leg, pelvic unleveling, and chronic back pain, including these:

-

- The Short Leg Syndrome in Obstetrics and Gynecology; Correction Of Anatomical Short Leg For The Treatment Of Back Pain; American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1970 (14)

- Low-back Pain Associated With Leg Length Inequality; Spine, 1981 (15)

- Clinical Symptoms and Biomechanics of Lumbar Spine and Hip Joint in Leg Length Inequality; Spine, 1983 (16)

- Persistent Low Back Pain and Leg Length Disparity; Journal of Rheumatology, 1985 (17)

- g Length Inequality and Low Back Pain;The Practitioner, 1985 (18)

- •Conservative Correction of Leg-Length Discrepancies of 10 mm or Less for the Relief of Chronic Low Back Pain; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2005 (19)

- •Changes in Pain and Disability Secondary to Shoe Lift Intervention in Subjects With Limb Length Inequality and Chronic Low Back Pain; Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2007 (20)

•••••

A recent (2016) study pertaining to the biomechanical consequences of an anatomical short leg was published in the Journal of Craniovertebral Junction Spine and titled (21):

Inequality in Leg Length is Important for the

Understanding of the Pathophysiology of Lumbar Disc Herniation

These authors evaluated 39 subjects with leg length discrepancy and low back pain and 43 controls to quantify the occurrence of disc herniation between between the two groups. They concluded that leg length inequality causes spinal joint load assymetry, accelerating disc degeneration and disc herniation. They also suggest the poor low back disc surgical outcomes may be linked to the abnormal spinal loads caused by leg length inequality, They note:

“Inequality in leg length may lead to abnormal transmission of load across the endplates [causing] degeneration of the lumbar spine and the disc space.”

“Human coronal balance may be one of the causes of operative failure after disc surgery. Assessment of pathologic coronal imbalance requires a clear understanding of normal coronal alignment.”

“Patients with chronic LBP have a minor balance defect. Inequality in leg length is important for the understanding of the pathophysiology of lumbar disc degeneration and herniation.”

“Our observations suggest that LBP may have etiologies related to abnormal load transmission due to coronal imbalance. It seems that a successful treatment may sometimes exist beyond good surgery. In these situations, abnormal coronal balance may be an important factor.”

•••••

This year (2017), an important article was published in the journal Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, titled (22):

Shoe Orthotics for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Randomized Controlled Trial

The objective of this study was to investigate the efficacy of shoe orthotics with and without chiropractic treatment for chronic low back pain as compared to no treatment. It is a Randomized Controlled Trial (three groups) that involved 225 adults with symptomatic low back pain of 3 months or longer:

Group 1:Orthotics Group

The Orthotics Group received custom-made shoe orthotics.

Group 2:Plus Group

Plus Group received custom-made orthotics plus chiropractic manipulation, hot or cold packs, and manual soft tissue massage.

Group 3:Wait Group

The Wait-list Group received no care.

Both pain levels and disability were assessed at 6 weeks and 12 weeks, and then after an additional 3, 6, and 12 months. These authors note:

“The best results were in the Orthotics Plus group in which 70% had a decrease in pain and 56% a decrease in disability of 30% or more compared to baseline.”

“This large-scale clinical trial demonstrated that LBP and disability were significantly improved after six weeks of orthotics care compared to a wait-list control, and that the addition of chiropractic care with the orthotics demonstrated a significant improvement in the disability scores compared to orthotics alone.”

“Six weeks of prescription shoe orthotics significantly improved back pain and dysfunction compared to no treatment. The addition of chiropractic care led to higher improvements in function.”

“Foot dysfunction should not be overlooked as a potential contributing factor in treating individuals with LBP and dysfunction.”

SUMMARY

These concepts and studies add support for why all people should be evaluated chiropractically for pelvic asymmetry and coronal misalignment; correction of such asymmetries and misalignment may prevent low back pain and disc disease/herniation, and improve surgical outcomes.

For individuals suffering from chronic low back pain, the combination of orthotics to improve foot pronation, heel lifts to compensate for anatomical leg length inequality, and chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific manipulations) to the spinal joints appears to be a biologically sound exceptional management approach.

References

- Rush WA, Steiner HA; A Study of Lower Extremity Length Inequality; American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy; Vol. 51; No. 5; November 1946; pp. 616-623.

- Lacayo R; How Sick Was J.F.K.?; TIME; November 24, 2002.

- Altman LK, Purdum TS; In J.F.K. File, Hidden Illness, Pain and Pills; The New York Times; November 17, 2002.

- Dallek R; The Medical Ordeals of JFK; The Atlantic; December 2002.

- Wilson V; Janet G. Travell, MD: A Daughter’s Recollection; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; Vol. 30; No. 1; pp. 8ñ12.

- Bagg JE; The President’s Physician; Texas Heart Institute Journal; 2003; Vol. 30; No. 1; pp. 1ñ2.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual; New York: Williams & Wilkins, 1983.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: THE LOWER EXTREMITIES; New York: Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

- Simons D, Travell J; Travell & Simons’, Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: Volume 1, Upper Half of Body; Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- Morton DJ; METATARSUS ATAVICUS: The Identification of a Distinctive Type of Foot Disorder; J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1927 Jul 01;9(3):531-544.

- Subotnick SI; Sports Medicine of the Lower Extremity; Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

- Friberg O; The statics of postural pelvic tilt scoliosis; a radiographic study on 288 consecutive chronic LBP patients; Clinical Biomechanics; Vol. 2; No. 4; November 1987; pp. 211-219.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume 3; The Trunk and the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- Sicuranza B, Richards J, Tisdall L; The Short Leg Syndrome in Obstetrics and Gynecology; American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology; May 15, 1970; Vol. 107; No. 2; pp. 217-219.

- Giles LG, Taylor JR; Low-back pain associated with leg length inequality; Spine; 1981 Sep-Oct; Vol. 6; No. 5; pp. 510-251.

- Friberg O; Clinical symptoms and biomechanics of lumbar spine and hip joint in leg length inequality; Spine; 1983 Sep; Vol. 8; No. 6; pp. 643-651.

- Gofton JP; Persistent Low Back Pain and Leg Length Disparity; Journal of Rheumatology; Vol. 12, No. 4; August 1985; pp. 747-750.

- Helliwell M; Leg Length Inequality and Low Back Pain; The Practitioner; May 1985; Vol. 229; pp. 483-485.

- Defrin R, Benyamin SB, Dov Aldubi R, Pick CG; Conservative Correction of Leg-Length Discrepancies of 10 mm or Less for the Relief of Chronic Low Back Pain; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; November 2005; Vol. 86; No. 11; pp. 2075-2080.

- Golightly YM, Tate JJ, Burns CB, Gross MT; Changes in Pain and Disability Secondary to Shoe Lift Intervention in Subjects With Limb Length Inequality and Chronic Low Back Pain; Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy; Vol. 37; No. 7; July 2007; pp. 380-388.

- Balik SM, Kanat A, Erkut A, Ozdemir B, Batcik OE; Inequality in Leg Length is Important for the Understanding of the Pathophysiology of Lumbar Disc Herniation; Journal of Craniovertebral Junction Spine April-June 2016; Vol. 7; No. 2; pp. 87-90.

- Cambron JA, Dexheimer JM, Duarte M, Freels S; Shoe Orthotics for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; April 29, 2017. [Epub]

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.