Pathoanatomy and Management Options Understanding the Upper Cervical Spine

The strict definition of migraine headache is (8):

- The headache must last 4 to 72 hours.

- The headache must be associated with nausea and/or vomiting, or photophobia, and/or phonophobia.

- The headache must be characterized by 2 of the following 4 symptoms:

-

- unilateral location

- throbbing pulsatile quality

- moderate or worse degree of severity

- intensified by routine physical activity

-

•••

The headline appearing in the Business Section of the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper on July 20, 2014, was alarming (1):

MEDICINE

Huge Headache of a Problem

Mastering Migraines Still a Challenge for Patients, Scientists

Author Stephanie Lee notes that 36 million Americans suffer from migraine headaches. The migraine market in developed countries will grow to about $5.4 billion in 2022. The problem is that current treatments are not very effective and they may have dangerous side effects. Ms. Lee notes (1):

“Frustrated patients often seek out opioids in the emergency room, but opioids can be dangerous. In a year, … 20,000 patients in California developed chronic migraines because of opioid overuse, and 3,000 become addicted.”

Chronic migraine is defined as a severe headache that occurs at least 15 times per month. It is ironic that opioids taken for migraines cause chronic migraines in so many patients. Ms. Lee concludes (1):

“The demand for safe and effective alternatives [for migraine headaches] is urgent.”

••••••••••

Morphine is the main chemical found in opium. Morphine is the gold standard of pain relieving drugs. It has been used for centuries, and medicine embraced it starting in 1817. It has been known for decades that morphine inhibits even the worst types of pain. In World War II, medics routinely administered morphine for horrific injuries to soldiers.

Endorphins are chemicals made in our bodies that also inhibit pain. Endorphin literally means “the morphines within.”(6) Endorphins suppress pain by binding to a receptor, called the opiate receptor.

The understanding of pain was advanced significantly in 1972 when graduate student Candace B. Pert discovered the brain’s opiate receptor. At the time, Ms. Pert was a graduate student working in the laboratory of Solomon Snyder, Ph.D., at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Ms. Pert’s paper on the opiate receptor was published the following year, in 1973, in the journal Science, and titled (2):

Opiate Receptor: Demonstration in Nervous Tissue

In 1974 Candace Pert earned a Ph.D. in pharmacology. In 1978, Dr. Pert’s co-author, Dr. Solomon Snyder, was awarded the prestigious Lasker Award for their work, overlooking Dr. Pert’s contribution, even though she was the paper’s primary author. Dr. Pert was angered by the oversight, and wrote about the experience in her 1997 book Molecules of Emotion (3). Despite the Lasker award slight, Dr. Pert’s career flourished, and she became one of the most important neuroscientists of history (d. 2013).

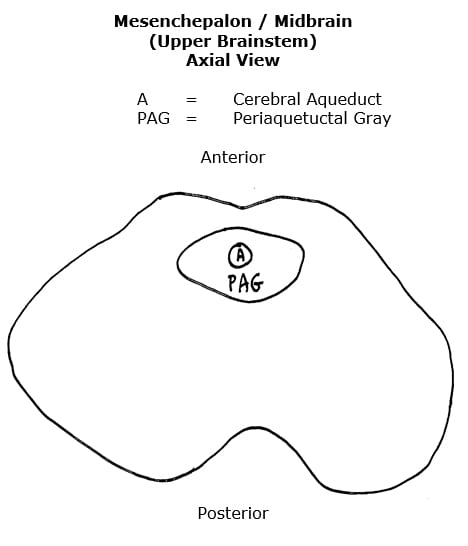

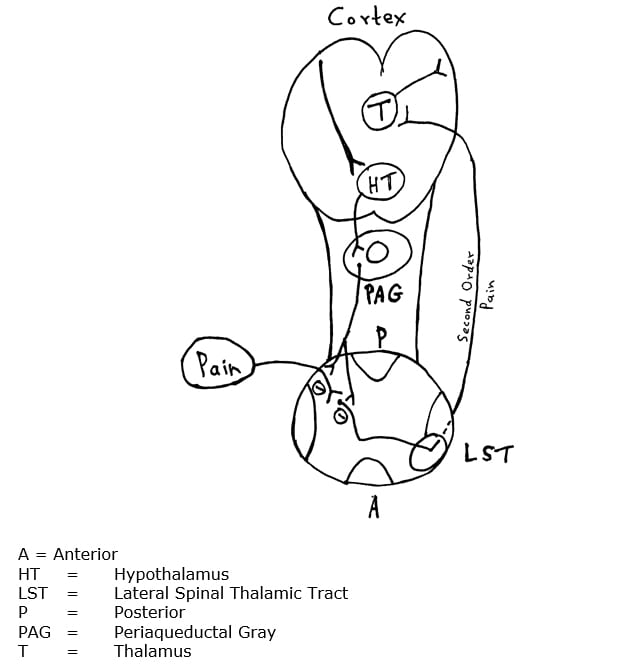

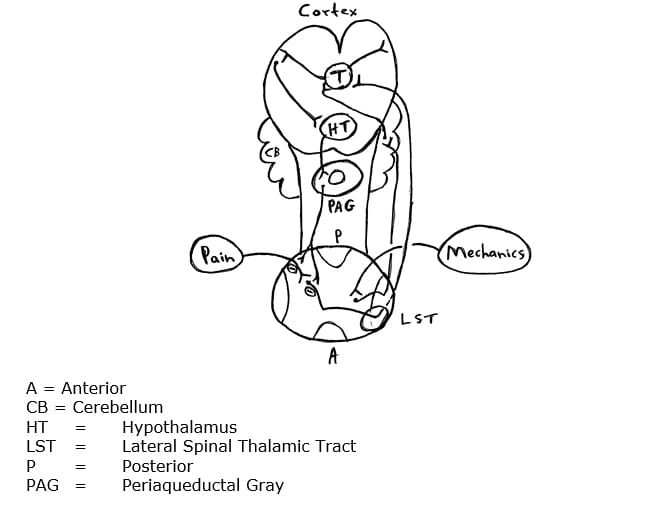

It was soon acknowledged that the spot most densely packed with opiate receptors was at the top of the brainstem, the periaqueductal gray matter of the mesencephalon (midbrain). The periaqueductal gray was considered to be the primary sight for pain control anywhere in the body. Initially, stimulating the periaqueductal gray chemically (with opioid drugs or electrically) was shown to suppress pain. Later, attention was turned to modalities such as acupuncture, massage, and spinal manipulation.

The pioneering paper using electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal gray matter to suppress pain was published in 1977 in the journal Science, and titled (4):

Pain Relief by Electrical Stimulation of the Central Gray Matter in Humans

This paper is nicely reviewed by neurobiologists Richard Restak, MD, in his 1979 book titled The Brain, The Last Frontier (5):

“Within the periaqueductal gray, a deep-seated brainstem area lying along the floor of the third ventricle, neurosurgeons at the University of California in San Francisco placed indwelling stimulating electrodes for pain relief in six patients afflicted with chronic, unremitting pain. Whenever the patients began to experience pain, they were able to shut it off via the activation of a battery-operated stimulator about the size of a pack of cigarettes. After activating the stimulator, all six patients—in accordance with earlier findings in other pain patients— experienced dramatic, long-lasting, and repeatable pain relief.”

“In order to test the hypothesis that pain relief was genuine and not just an example of a ‘placebo response,’ one patient was outfitted with a stimulator containing a ‘dead’ battery. The patient, a fifty-one-year-old woman with severe back and leg pain caused by cancer of the colon, anxiously reported that her pain had returned and the stimulator ‘wasn’t working.’ Replacement of a new battery led to immediate pain relief.”

Today, it is well established that the periaqueductal gray matter is the primary sight for whole body pain control. Using the words “periaqueductal gray pain” in PubMed locates 1470 references (as of August 7, 2014).

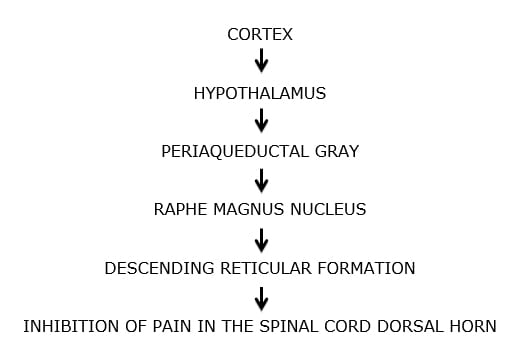

Contemporary neurology reference texts detail the importance of the opiate receptor and the periaqueductal gray matter in pain control (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). In general, they describe this sequence:

Although this sequence has a number of synonyms, classic terminology is the Descending Pain Inhibitory Control System.

••••••••••

Stimulating the Descending Pain Inhibitory Control System with opiate pharmacology has problems. There are opiate receptors throughout the central nervous system and opiate drugs influence these other receptor sites. Often, the patient would become “high” from these drugs, and patients would begin to consume these drugs for purposes other than pain control. The getting “high” practice is difficult to control; thousands of babies are born addicted to their mother’s opiate pill habit (12). Radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh risked his reputation, fame, fortune, and freedom in an effort to have a staff person purchase huge quantities of opiate drugs, a habit that apparently began when he was given a prescription for a back problem (13).

In a related story, addiction to opiate drugs is a serious and common problem. In May 2014, the newspaper USA Today quantified the problem noting (14):

- Hundreds of thousands of the nation’s seniors are misusing prescription drugs, including narcotic painkillers, anxiety medications and other pharmaceuticals, for everything from joint pain to depression.

- Over time, patients build up a tolerance to opiate drugs, or suffer more pain, and they ask for more medication.

- The 55 million opioid prescriptions written last year for people 65 and over marked a 20% increase over five years — nearly double the growth rate of the senior population.

- In 2012, the average number of seniors misusing or dependent on prescription pain relievers in the past year grew to an estimated 336,000, up from 132,000 a decade earlier.

These addictions are ruining many lives. When the supply of physician prescribed opiates declines, those addicted often turned to street drugs such as heroin or cocaine. Many turned to crimes to finance their habits. Opiate drug addictions are extremely difficult to conquer.

As noted by Stephanie Lee above, taking opiates for migraine causes a worsening of the headache to the status of chronic migraine in a substantial number of individuals (1).

•••••

Stimulating the Descending Pain Inhibitory Control System electrically is also problematic. Electrodes must be placed literally deep into the brainstem to access the periaqueductal gray matter. Such a procedure is logistically difficult to perform and is associated with substantial risks.

•••••

A much less invasive yet effective method of stimulating the Descending Pain Inhibitory Control System is with the use of acupuncture (15). The use of acupuncture for this purpose is well detailed in the 2000 book by Stux, titled Clinical Acupuncture, Scientific Basis, published in 2000 (16).

•••••

In 1996, Bill Vicenzino and colleagues from the University of Queensland, Australia, added significantly to the understanding of the mechanism of pain control through the use of spinal manipulation (adjusting) (17). Vicenzino and colleagues produced a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial using cervical spine manipulation (adjustment) on 15 subjects with lateral epicondylalgia (elbow pain). These authors cite references to support that the “clinical efficacy of manipulative therapy has been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials which report benefits in terms of pain relief and more rapid restoration of function.”

Their study showed a clear hypoalgesic effect from the use of spinal manipulation (adjusting). The results showed a “significant treatment effect beyond placebo or control.” The authors concluded: “manipulative therapy is capable of producing improvements in pain and function immediately following application.”

These authors made several astute and important observations, including:

- The subjects were suffering from elbow pain, NOT neck pain.

- The manipulation was applied to hypomobile joints of the cervical spine, NOT to the elbow.

- The improvement in elbow pain and function occurred immediately following the cervical spine manipulation, an improvement that is not explainable by the reduction of elbow inflammation or by accelerated elbow tissue healing.

- The descending pain inhibitory system is activated by stimulation of the periaqueductal gray matter.

Based upon these factors, and others, the authors concluded:

“These findings indicate that manipulative therapy may constitute an adequate physical stimulus for activating the descending pain inhibitory system.”

“… manipulative therapy recruits the descending pain inhibitory system, through which it exerts a portion of all of its pain relieving effects. That is, manipulative therapy applied to the cervical spine produces a sensory input which could be sufficient to activate the descending pain inhibitory system.”

•••••

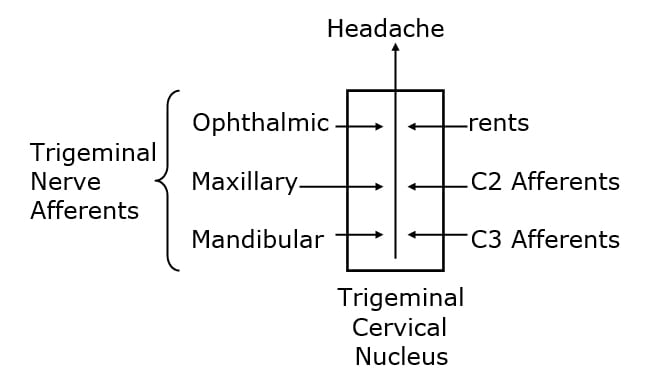

The brainstem and the upper spinal cord have a region of gray matter called the trigeminocervical nucleus. The nucleus is so named because its primary sensory inputs arise from the branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) and those of the upper cervical spine. In 1995, Nikoli Bogduk, MD, PhD, notes that all headaches, regardless of type, including migraine, synapse in the trigeminocervical nucleus (18).

Most recently (July 2014), Nelly Boyer and colleagues from Clermont University in France, have indicated that migraine headache progression is attributed to impairment of the descending pain inhibitory system to the trigeminocervical nucleus (19).

Also, recently (June 2014), Dean Watson and Peter Drummond from Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia, published a study in the journal Headache, titled (20):

Cervical Referral of Head Pain in Migraineurs:

Effects on the Nociceptive Blink Reflex

This study assessed the pain intensity and nociceptive blink reflex in 15 migraine subjects between times of symptoms with passive movements of the occipital and upper cervical spinal segments. The nociceptive blink reflex was elicited with a supraorbital electrical stimulus. The number of blinks of the nociceptive blink reflex were recorded. Head pain intensity was graded from 0-10, where 0 = “no pain” and 10 = “intolerable pain.” They note:

- Anatomical and neurophysiological studies show that there is a functional convergence of trigeminal and cervical afferent pathways.

- Migraine patients often have occipital and neck symptoms, with cervical pain being referred to the head, “suggesting that cervical afferent information may contribute to [migraine] headache.”

- Nerve blocks of the greater occipital nerve [C-2] modulate migraine pain, demonstrating a role for cervical afferents in migraine.

- “Spinal mobilization is typically applied when dysfunctional areas of the vertebral column are found.” “The clinician’s objective in applying manual techniques is to restore normal motion and normalize afferent input from the neuromusculoskeletal system.”

- There is a functional influence on trigeminal nociceptive inputs from cervical afferents. This study showed that passive manual intervertebral movement between the occiput and the upper cervical spinal joints decreases excitability of the trigeminocervical nucleus.

- “Our findings corroborate previous results related to anatomical and functional convergence of trigeminal and cervical afferent pathways in animals and humans, and suggest that manual cervical modulation of this pathway is of potential benefit in migraine.” [emphasis added]

- These findings show that “cervical spinal input contributed to lessening of referred head pain and cervical tenderness.”

These authors conclude:

Ongoing noxious sensory input arises from biomechanically dysfunction spinal joints. Mechanoreceptors including proprioceptors (muscle spindles) within deep paraspinal tissues react to mechanical deformation of these tissues. Manual mechanical deformation can cause “biomechanical remodeling” with restoration of zygapophyseal joint mobility and joint “play.” “Biomechanical remodeling resulting from mobilization may have physiological ramifications, ultimately reducing nociceptive input from receptive nerve endings in innervated paraspinal tissues.”

These findings “corroborate previous results related to anatomical and functional convergence of trigeminal and cervical afferent pathways in animals and humans, and suggest that manual modulation of the cervical pathway is of potential benefit in migraine.”

SUMMARY

- The universal spot for pain control is in the upper brainstem, the periaqueductal gray matter.

- The periaqueductal gray matter, when stimulated directly or via the hypothalamus initiates the descending pain inhibitory system.

- All headaches, including migraine headaches, synapse in the neck, in a spot called the trigeminocervical nucleus. As its name implies, the trigeminocervical nucleus also receives input from the upper cervical spine sensory fiends, via C1-C2-C3 nerve roots.

- Migraine headache sufferers have impairment of the descending pain inhibitory system.

- Improvement of the mechanical function of the joints and tissues of the upper cervical spine reduces migraine headache pain. It probably does so by stimulating the descending pain inhibitory system to the trigeminocervical nucleus.

- Upper cervical spine manual therapy and adjustments improve mechanical function, reducing migraine headache pain. It probably does so by stimulating the descending pain inhibitory system to the trigeminocervical nucleus.

These studies explain what essentially every chiropractor has observed:

Improvement of the mechanical function of the upper cervical spine inhibits nociceptive input from the upper cervical spine into the trigeminal cervical nucleus, reducing its central sensitization, reducing the nociceptive signal on the second order neuron to the brain for the perception of headache.

REFERENCES

- Lee, SM; Huge Headache of a Problem; Mastering Migraines Still a Challenge for Patients, Scientists; San Francisco Chronicle; July 20, 2014; pp. D1 and D5.

- Pert CB, Snyder SH; Opiate receptor: demonstration in nervous tissue; Science; 1973 Mar 9;179(4077):1011-4.

- Pert CB; Molecules of Emotion, The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine; Touchstone Books; 1997.

- Hosobuchi Y, Adams JE, Linchitz R; Pain relief by electrical stimulation of the central gray matter in humans and its reversal by naloxone; Science; 1977 Jul 8;197(4299):183-6.

- Richard Restak, MD; The Brain, The Last Frontier, Warner Books, 1979; pp. 341-342.

- Raymond D Adams, MD; Maurice Victor, MD; Allan H Ropper, MD; Principles of Neurology; Sixth Edition; 1977.

- Eric R Kandel, James M Schwartz, Thomas M Jessell; Principles of Neural Science; Fourth Edition; 2000.

- H Royden Jones, MD; Netter’s Neurology; 2005.

- Marco Pappagallo; The Neurological Basis of Pain; 2005.

- Stephen B McMahon; Martin Koltzenburg, MD; Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain; Fifth Edition; 2006

- Randy W Beck; Functional Neurology for Practitioners of Manual Therapy; 2008.

- Szabo L; Number of Painkiller-Addicted newborns triples in 10 years; USA Today; May 1, 2012.

- John J. Goldman and Steve Carney; Limbaugh Admits Painkiller Addiction; The Los Angeles Times; October 11, 2003.

- Peter Eisier; Medication Generation, Seniors Misusing Prescription Drugs; USA Today; May 22, 2014.

- Takeshige C, Sato T, Mera T, Hisamitsu T, Fang J; Descending pain inhibitory system involved in acupuncture analgesia; Brain Research Bull; 29 (1992); pp. 617-634.

- Stux G, Hammerschlag R (Eds); Clinical Acupuncture, Scientific Basis, Springer, 2000.

- Vicenzino B, Collins D, Wright A; The initial effects of cervical spine manipulative physiotherapy treatment on the pain and dysfunction of lateral epicondylalgia; Pain; Vol. 68 (1996); pp. 69-74.

- Bogduk N; Anatomy and Physiology of Headache; Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy; 1995, Vol. 49, No. 10, 435-445.

- Boyer N, Dallel R, Artola A, Monconduit L; General trigeminospinal central sensitization and impaired descending pain inhibitory controls contribute to migraine progression; Pain 2014; Vol. 155; pp. 1196-1205.

- Watson DH, Drummond PD; Cervical Referral of Head Pain in Migraineurs: Effects on the Nociceptive Blink Reflex; Headache 2014; Vol. 54; pp. 1035-1045.

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.