The headlines in the lay press are troubling and disturbing. A front section full-page in the newspaper Wall Street Journal showing a person clenching their back while proclaiming (1):

“More Than 100 Million American Adults Live with Chronic Pain”

Another cover study in the Wall Street Journal quantifying the anatomical regions for American’s chronic pain (2):

Hip Pain 07.1%

Finger Pain 07.6%

Shoulder Pain 09.0%

Neck Pain 15.1%

Severe Headache 16.1%

Knee Pain 19.5%

Lower-Back Pain 28.1%

An editorial discussion in the newspaper USA Today, referencing the Institutes of Medicine of the United States noting (3):

“One hundred sixteen million Americans suffer from chronic pain, costing the US up to $635 billion in treatment and lost productivity. Chronic pain even increases the risk of depression and suicide.”

These appalling numbers indicate that more than a third of all Americans, and more than half of American adults, suffer from chronic daily pain. More than a quarter of this chronic pain is located in the low back.

••••••••••

For decades, conventional wisdom pertaining to Low Back Pain (LBP) has been that the great majority (90%) of this pain will resolve quickly (within two months) with no treatment or with any form of treatment. This “wisdom” became entrenched in the minds of health care providers, insurance companies, government bodies and practice guidelines after it was succinctly stated by the exceptional spine care pioneer Alf Nachemson, MD, PhD, in the debut issue of the journal SPINE in 1976. Dr. Nachemson stated (4):

“Irrespective of treatment given, 70% of [back pain] patients get well within 3 weeks, 90% within 2 months.”

A few years later (1979 first edition, 1990 second edition), the authoritative reference text Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, is published (5). Written by Harvard’s Augustus White, MD, and Yale’s Manohar Panjabi, PhD, the text reiterates Dr. Nachemson’s message, stating:

“There are few diseases [low back pain] in which one is assured improvement of 70% of the patients in 3 weeks and 90% of the patients in two months, regardless of the type of treatment employed.”

Therefore, “it is possible to build an argument for withholding treatment.”

This “quick recovery regardless of treatment conventional wisdom” pertaining to low back pain was fervently challenged in 1998 by Peter R. Croft, PhD, and colleagues. Dr. Croft is a Professor of Primary Care Epidemiology at KeeleUniversity in Staffordshire, UK. Dr. Croft and colleagues published their work in 1998 in the British Medical Journal in an article titled (6):

Outcome of Low back Pain in General Practice:

A Prospective Study

These authors evaluated the statistics on the natural history of low back pain, noting that it is widely believed that 90% of episodes of low back pain seen in general practice resolve within one month. They consequently investigated this claim by prospectively following 463 cases of acute low back pain for a year.

These researchers discovered that 92% of these low back pain subjects ceased to consult their primary physician about their low back symptoms within three months of onset; they were no longer going to their doctor for low back pain treatment. Yet, most of them still had substantial low back pain and related disability. Only 25% of the subjects who consulted about low back pain had fully recovered 12 months later; 75% had progressed to chronic low back pain sufferers, but they were no longer going to their doctor!

This study is adamant that NOT seeing a doctor for a back problem does NOT mean that the back problem has resolved. This study showed that 75% of the patients with a new episode of low back pain have continued pain and disability a year later, even though most are not continuing to go to the doctor. They conclude that the belief that 90% of episodes of low back pain seen in general practice resolve within one month is false.

The belief that most low back pain episodes will be “short lived and that ‘80-90% of attacks of low back pain recover in about six weeks, irrespective of the administration or type of treatment’” is untrue, false. Many patients seeing their general practitioner for the first time in an episode of back pain will still have pain or disability 12 months later but will not be consulting their doctor about it. Low back pain should be viewed as a chronic problem with an untidy pattern of grumbling symptoms and periods of relative freedom from pain and disability interspersed with acute episodes, exacerbations, and recurrences.

Important quotes from this article include:

“It is generally believed that most of these episodes [of low back pain] will be short lived and that ‘80-90% of attacks of low back pain recover in about six weeks, irrespective of the administration or type of treatment.’”

“By three months after the [initial] consultation with their general practitioner, only a minority of patients with low back pain had recovered.”

“There was little increase in the proportion who reported recovery by 12 months, emphasizing the recurrent and persistent nature of this [low back pain] problem.”

“The findings of our interview study are in sharp contrast to the frequently repeated assumption that 90% of episodes of low back pain seen in primary care will have resolved within a month.”

“However, the results of our consultation figures are consistent with the interpretation that 90% of patients presenting in primary care with an episode of low back pain will have stopped consulting about this problem within three months of their initial visit.”

“The inference that the patients have completely recovered [because they have stopped going to the doctor] is clearly not supported by our data.”

“We should stop characterizing low back pain in terms of a multiplicity of acute problems, most of which get better, and a small number of chronic long term problems. Low back pain should be viewed as a chronic problem with an untidy pattern of grumbling symptoms and periods of relative freedom from pain and disability interspersed with acute episodes, exacerbations, and recurrences. This takes account of two consistent observations about low back pain: firstly, a previous episode of low back pain is the strongest risk factor for a new episode, and, secondly, by the age of 30 years almost half the population will have experienced a substantive episode of low back pain. These figures simply do not fit with claims that 90% of episodes of low back pain end in complete recovery.”

••••••••••

In 2003, Lise Hestbaek, DC, PhD, and colleagues from the University of Southern Denmark published a study in the European Spine Journal, titled (7):

Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations

These authors performed a comprehensive review of the literature on this topic, noting “it is often claimed that up to 90% of low back pain (LBP) episodes resolve spontaneously within 1 month.” They used 36 articles that met their criteria. The tabulated results showed that on average 62% (range 42-75%) still experienced pain after 12 months. The authors concluded:

“The overall picture is that LBP does not resolve itself when ignored.”

“The overall picture is clearly that LBP is not a self-limiting condition. There is no evidence supporting the claim that 80– 90% of LBP patients become pain free within 1 month.”

••••••••••

Ronald Donelson, MD, is a Board Certified Orthopedic Surgeon and the current Vice President of the American Back Society. Dr. Donelson is associated with the State University of New Youk, in Syracuse. In 2102, Dr. Donelson and colleagues published a study in the journal Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, titled (8):

Is It Time to Rethink the Typical Course of Low Back Pain?

The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency and the characteristics of low back pain (LBP) recurrences by asking these questions:

1) Are low back pain (LBP) recurrences common?

2) Do episodes worsen with multiple recurrences?

Questionnaires were given to 589 LBP patients from 30 clinical practices (primary care [7%], physical therapy [67%], chiropractic [19%], and surgical spine [7%]) in North America and Europe. The results were:

1) Are low back pain (LBP) recurrences common?: [rounded]

73% had suffered a previous episode of LBP

54% had experienced ≥10 episodes of prior LBP in their lifetime

20% had experienced >50 episodes of prior LBP in their lifetime

27% with a previous episode of LBP had 5 or more episodes of LBP per year

2) Do LBP episodes worsen with multiple recurrences?: [rounded]

61% reported in the affirmative

Dr. Donelson and colleagues are critical of clinical practice guidelines that characterize the typical course of LBP as benign and favorable, stating:

“It is often stated that LBP is normal; has an excellent prognosis, with 90% of individuals recovering within 3 months of onset in most cases; and is not debilitating over the long term. One guideline states that recovery usually takes place within as little as 6 weeks.”

“Acute LBP is perceived as largely self-limiting and requiring little if any formal treatment. This benign view justifies what has become the standard clinical guideline recommendation that clinicians often need do nothing more than simply reassure patients that they will likely recover.”

“In any one year, recurrences, exacerbations, and persistence dominate the experience of low back pain in the community. This clinical picture is very different from what is typically portrayed as the natural history of LBP in most clinical guidelines.”

They note that few clinicians realize that this positive recovery prognosis was derived from flawed protocols:

1) When patients with LBP did not return for follow-up assessment, the researchers assumed that the patients had recovered. It is now known that the failure of a patient with acute LBP to return to the same doctor “does not necessarily indicate recovery.” “A patient’s disappearance from the practice is a poor proxy for recovery.” When persistent LBP does not respond to a doctor’s care, the patient tends to drop out of care.

2) A number of studies used the “ability to return to work” as a proxy for recovery, even if the patient has substantial low back pain.

Dr. Donelson and colleagues note:

“Recurrences of back pain are widely recognized as common, reported as occurring in 60%-73% of individuals within 1 year after recovery from an acute episode.”

“Consistent with many other published studies, the recurrence rate among our respondents with LBP was 73%.”

“Most persistent disabling back pain is preceded by episodes that, although they may resolve completely, may also increase in severity and duration over time.”

“Many patients with chronic LBP had prior recurrent episodes that had become longer and more severe until the most recent episode did not resolve and thus became chronic.”

“The conventional view of the natural history of acute LBP is that it is self-limiting and that 90% of patients experiencing LBP recover within 90 days or less, but there is no evidence to suggest that either of these statements is accurate. In reality, the recovery rates reported in population studies and in our survey data are far less optimistic.”

“Collectively, our findings, and those of other studies, indicate that it may be inaccurate to characterize LBP as having an excellent prognosis. Recurrences are frequent and are often progressively worse over time. Recovery from acute LBP is not as favorable as is routinely portrayed.”

“Eventually, there may be no recovery, and the underlying condition may become chronically painful. In light of these characteristics, it seems inappropriate to characterize the natural history of LBP as benign and favorable.”

••••••••••

In 2013, Coen J. Itz, PhD, and colleagues from the Department of Health Service Research, MaastrichtUniversity, The Netherlands, published a study in the European Journal of Pain, titled (9):

Clinical Course of Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies set in Primary Care

Dr. Itz and colleagues performed a systematic literature review investigating the clinical course of pain in patients with non-specific acute low back pain that obtained treatment in primary care. All included studies were prospective studies, with follow-up of at least 12 months. Proportions of patients still reporting pain during follow-up were pooled. A total of 11 studies were eligible for evaluation. In the first 3 months, recovery was observed in 33% of patients, but the pooled proportion of patients still reporting pain after 1 year was 71%. These authors state:

“Non-specific low back pain is a relatively common and recurrent condition for which at present there is no effective cure.”

“In current guidelines, the prognosis of acute non-specific back pain is assumed to be favorable.”

These authors conclude:

“The findings of this review indicate that the assumption that spontaneous recovery occurs in a large majority of patients is not justified.”

Importantly, these authors emphasize that there should be more focus on intensive follow-up of patients who have not recovered within the first 3 months following an episode of acute low back pain.

••••••••••

Kate Dunn, PhD, is an epidemiologist working at the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, KeeleUniversity, Staffordshire, UK. In 2013, Dr Dunn and colleagues published a study in the journal Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, titled (10):

Low Back Pain Across the Life Course

Dr. Dunn and colleagues note that people with pain continue to have it on and off for years. They state:

“Back pain episodes are traditionally regarded as individual events, but this model is currently being challenged in favor of treating back pain as a long-term or lifelong condition. Back pain can be present throughout life, from childhood to older age, and evidence is mounting that pain experience is maintained over long periods.”

Dr. Dunn and the other articles referenced above all make the same central points. They are, as a rule, acute non-specific low back pain is not self limiting, it is more likely than not to become chronic, when it becomes asymptomatic recurrences are very common, each recurrence tends to become worse, and the solution is to administer a long-term management strategy that alters the pathophysiological process.

••••••••••

SOLUTIONS

In 2011, Manuel Cifuentes, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Center for Disability Research at the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety, Hopkinton, MA, USA, published a study in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, titled (11):

Health Maintenance Care in Work-Related Low Back Pain and Its Association With Disability Recurrence

Dr. Cifuentes and colleagues compared the occurrence of repeated disability episodes across types of health care providers who treat claimants with new episodes of work-related low back pain (LBP). The providers evaluated were medical physicians, physical therapists, and chiropractors. A total of 894 cases were followed for 1-year using workers’ compensation claims data.

Dr. Cifuentes and colleagues note that low back pain is one of the costliest work-related injuries in the United States in terms of disability and treatment costs. Yet, there has been little success in preventing recurrent LBP. Specifically, as noted in their title, these authors evaluate the efficacy of “heath maintenance” in the prevention of recurrent LBP.

Health maintenance care is defined as treatment after optimum recorded benefit has already been reached. Health maintenance care can include providing advice, information, counseling, and specific physical procedures. Health maintenance care is “predominantly and explicitly recommended by chiropractors who advocate health maintenance procedures to prevent recurrences.”

This study showed that in the treatment of Workers Compensation low back injury that:

1) Chiropractically managed patients are significantly less likely to have a recurrence of low back pain.

2) Chiropractically managed patients that do have a recurrence of low back pain do so an average of 29 days later than those treated by a physical therapist or medical doctor.

3) Chiropractically managed patients have shorter periods of disability, meaning they returned to work earlier.

4) Chiropractic patients had “fewer surgeries, used fewer opioids, and had lower costs for medical care than the other provider groups.”

5) The reduced recurrence of low back disability is the consequence of “chiropractic treatment.”

6) Chiropractic patients had “less expensive medical services and shorter initial periods of disability than cases treated by other providers.”

These authors state:

“After controlling for demographics and severity indicators, the likelihood of recurrent disability due to LBP for recipients of services during the health maintenance care period by all other provider groups was consistently worse when compared with recipients of health maintenance care by chiropractors.”

“This clear trend deserves some attention considering that chiropractors are the only group of providers who explicitly state that they have an effective treatment approach to maintain health.”

“Our results, which seem to suggest a benefit of chiropractic treatment to reduce disability recurrence, imply that if the benefit is truly coming from the chiropractic treatment, there is a mechanism through which care provided by chiropractors improves the outcome.”

“Our findings seem to support the use of chiropractor services, as chiropractor services generally cost less than services from other providers.”

Dr. Cifuentes and colleagues speculate that the main advantage of chiropractors could be based on the dual nature of their practice: regular care plus maintenance care.

••••••••••

In 2011, Mohammed K. Senna MD, Shereen A. Machaly, MD, published a study in the journal SPINE, titled (12):

Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Result in Better Long-Term Outcome?

Randomized Trial

Drs. Senna and Machaly are “MD certified, well-trained, have been in practice for more than 10 years with good experience in managing LBP, and they are staff members of Rheumatology & Rehabilitation Department, Mansoura University [Egypt].”

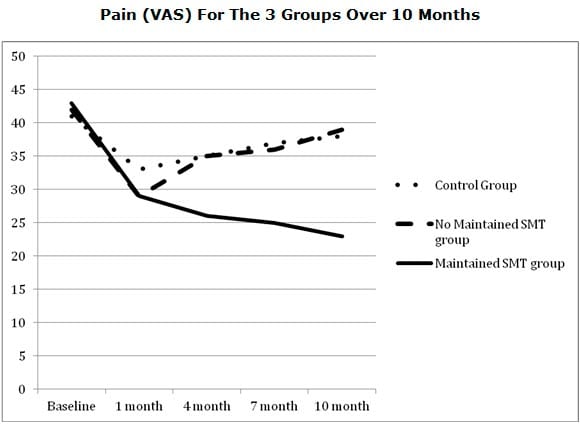

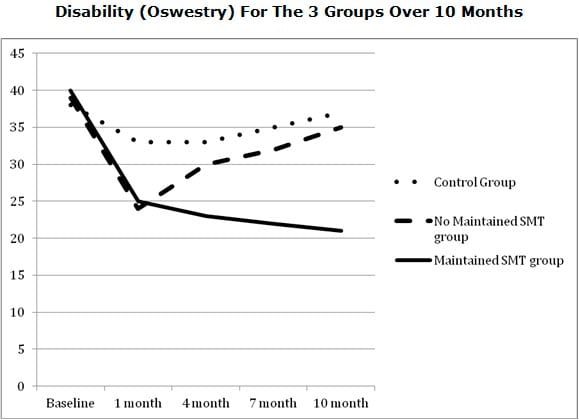

This prospective single blinded placebo controlled study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain (LBP) and to determine the effectiveness of maintenance SMT in long-term reduction of pain and disability levels associated with chronic low back conditions. The spinal manipulation was defined as a “high velocity thrust to a joint beyond its restricted range of movement.”

Sixty patients with chronic, nonspecific LBP lasting at least 6 months, were randomized to receive either:

a) 12 treatments of sham SMT over a 1-month period

b) 12 treatments consisting of SMT over a 1-month period

c) 12 SMT treatments over a 1-month period plus maintenance SMT every 2 weeks for the following 9 months

Follow-up evaluations occurred at 1, 4, 7, and 10-months, assessing:

a) Pain (Visual Analog Scale [VAS]

The “VAS is a valid tool to indicate the current intensity of pain.”

b) Disability [Oswestry Disability Questionnaire]

The Oswestry disability questionnaire has been shown to be a valid indicator of disability in patients with LBP.

c) Generic health [SF-36]

The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) measures eight dimensions: general health perception, physical function, physical role, bodily pain, social functioning, mental health, emotional role, and vitality. “The SF-36 is a valid and reliable instrument widely used to measure generic health status, particularly for monitoring clinical outcomes after medical interventions.”

Results:

Patients receiving real manipulation “experienced significantly lower pain and disability scores” than patients receiving sham manipulation at the end of 1-month. Only the group that was given maintenance spinal manipulations showed more improvement in pain and disability scores at the 10-month evaluation. In the non-maintained SMT group, the mean pain and disability scores returned back near to their pretreatment level. The authors concluded:

“This study confirms previous reports showing that SMT is an effective modality in chronic nonspecific LBP.”

“SMT is effective for the treatment of chronic nonspecific LBP. To obtain long-term benefit, this study suggests maintenance SMT after the initial intensive manipulative therapy.”

“One possible way to reduce the long-term effects of LBP is maintenance care (or preventive care).”

••••••••••

Nonspecific chronic LBP is not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology (such as infection, tumor, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, radicular syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome). It represents about 85% of LBP patients seen in primary care. About 10% of these patients will go on to develop chronic, disabling LBP, using the majority of health care and socioeconomic costs. Eighty-four percent of total medical costs for patients with LBP are related to back pain recurrence. The studies presented support using spinal manipulation for both acute and chronic non-specific low back pain, as well as using maintenance spinal manipulation to reduce the incidence of back pain recurrence and its associated costs.

REFERENCES

1) Foreman J; Why Women are Living in the Discomfort Zone; More Then 100 Million American Adults Live with Chronic Pain—Most of them Women. What will it take to bring them relief?; January 31, 2014.

2) Wang S; Why Does Chronic Pain Hurt Some People More?; Wall Street Journal; October 7, 2013.

3) Pho, K; USA TODAY, The Forum; September 19, 2011; pg. 9A.

4) Nachemson, Alf, MD, PhD; The Lumbar Spine, An Orthopedic Challenge; SPINE Volume 1, Number 1, March 1976, Pages 59-71.

5) White AA, Panjabi MM, Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, Second Edition, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1990.

6) Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ; Outcome of Low Back Pain in General Practice: A Prospective Study; British Medical Journal; May 2, 1998; Vol. 316, pp. 1356-1359.

7) Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C; Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations; European Spine Journal; April 2003; Vol. 12; No 2; pp. 149-65.

8) Donelson R, McIntosh G; Hall H; Is It Time to Rethink the Typical Course of Low Back Pain?; Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R); Vol. 4; No. 6; June 2012, Pages 394–401.

9) Itz CJ, Geurts JW, van Kleef M, Nelemans P; Clinical course of non-specific low back pain: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies set in primary care; European Journal of Pain; January 2013;Vol. 17; No. 1; pp. 5-15.

10) Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, Cassidy JD; Low back pain across the life course;Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology; October 2013; Vol. 27; No. 5; pp. 591-600.

11) Cifuentes M, Willetts J, Wasiak R; Health Maintenance Care in Work-Related Low Back Pain and Its Association With Disability Recurrence; Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; April 14, 2011; Vol. 53; No. 4; pp. 396-404.

12) Senna MK, Machaly SA; Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Result in Better Long-Term Outcome? Randomized Trial; SPINE; August 15, 2011; Volume 36, Number 18, pp. 1427–1437.

Thousands of Doctors of Chiropractic across the United States and Canada have taken "The ChiroTrust Pledge":

“To the best of my ability, I agree to

provide my patients convenient, affordable,

and mainstream Chiropractic care.

I will not use unnecessary long-term

treatment plans and/or therapies.”

To locate a Doctor of Chiropractic who has taken The ChiroTrust Pledge, google "The ChiroTrust Pledge" and the name of a town in quotes.

(example: "ChiroTrust Pledge" "Olympia, WA")

Content Courtesy of Chiro-Trust.org. All Rights Reserved.